A 105th Annual Meeting Session Spotlight

By guest author Jacques Gordon, Director, Graaskamp Center for Real Estate, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Editor’s note: The “Panel Discussion in Climate Linked Economics: Navigating Climate Risks and Economic Shifts in Real Estate” takes place today, Monday 13 January, at 4:30 p.m. as part of the New Orleans Forum on Climate Linked Economics at the 105th AMS Annual Meeting.

My apartment in Boston’s Back Bay is just across the Boston Common from the AMS headquarters on Beacon Street. Yet, when Brock Burghart invited me to speak at the Annual Meeting, I knew very little about the organization—its history, its journals, or its purpose.

In registering for the conference and exploring the AMS website, I reached a number of quick conclusions.

- Serious climate scientists and the broader world of weather fanatics all find a home at AMS.

- The organization is committed to education, research, and networking.

- I should join.

I have spent the last 40 years working in the field of real estate investment management on behalf of large institutions, like pension plans and sovereign wealth funds. Then, more recently, I joined two universities (MIT and Wisconsin) to help teach the next generation of real estate practitioners. It did not occur to me that the AMS would be a place where I could learn something I wanted to know or contribute something that might be of interest to others. By attending my first meeting, I am hoping to find out if either proposition is true.

My participation is part of the research track entitled “Climate-Linked Economics.” The panel I will serve on includes a risk management expert from Europe, a data scientist from Utah, and a housing data expert.

The material I plan to share follows directly from several different experiences that I have had in the investment industry and academia.

- Fifteen years ago, I co-founded the climate risk task force at the large investment management firm where I worked. Our goal was to link up the work of our risk management specialists, our portfolio managers, our research teams, and our deal-vetting acquisitions department. After Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, we knew we had to pay attention.

- Then, when I semi-retired as an “executive in residence” at MIT’s Center for Real Estate, I joined an interdisciplinary seminar with the grand-sounding name “The MIT Joint Program on Global Change.” This group of scientists from the Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Science department also teamed up with economists and social scientists to model the long-term effects of climate change.

- Finally, I recently moved to the Wisconsin School of Business, to lead its top-ranked real estate program and to make connections with faculty, alumni, and students. One of my first initiatives was to meet with as many of the alumni of both MIT and Wisconsin in Southern California as I could. We picked Santa Monica as our venue in mid-December of 2024. You can just imagine the dialogue over the past week between our alumni and the owners, developers, and financiers of residential and commercial real estate in this part of the world.

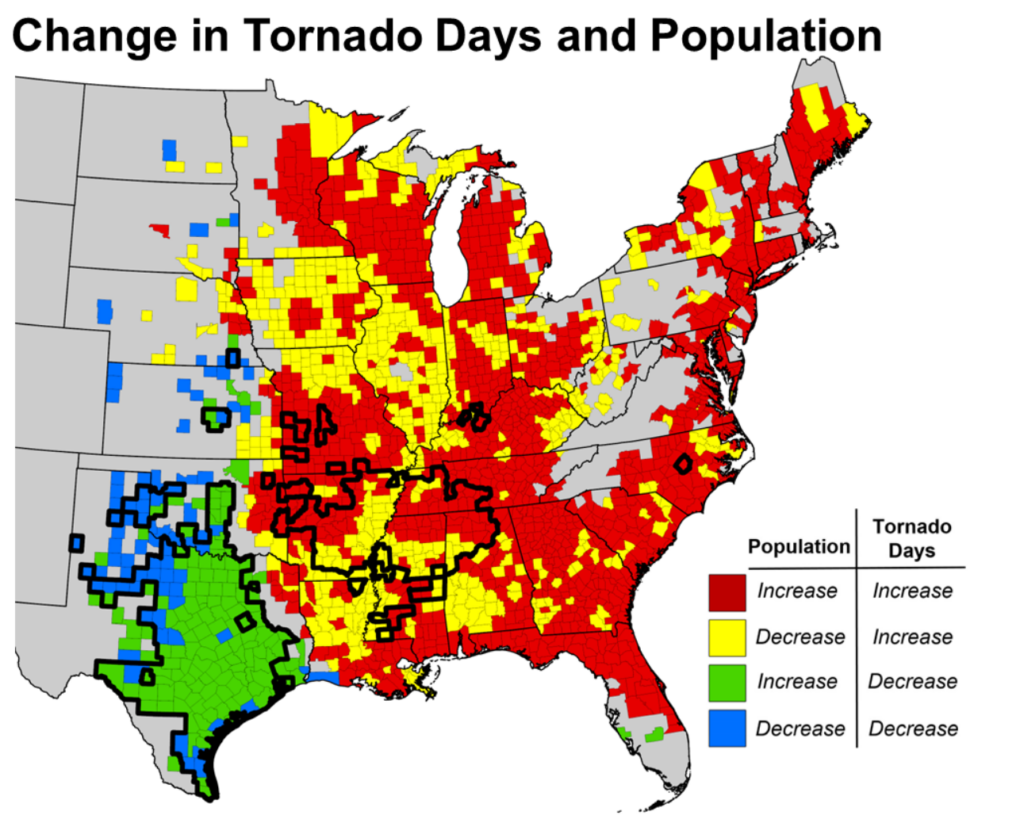

The massive move of American businesses and households to the sunbelt, where higher levels of climate risk are found, along with the increasing cost of insurance, and (most recently) the wildfires sweeping across the LA metro, all shape my views on how real estate and climate change intersect. Here are six take-aways that I plan to share with the AMS membership.

- Major weather events are costing property owners, the government, and insurers well over $1 trillion each year in the US. This is roughly equivalent to 4% of the national output of the country. Moreover, this estimate does NOT include the thousands of incidents of smaller (less than $1billion) weather-related damage that occur each year. Nor does it account for the rising cost of insurance—or the loss in a property’s value when insurance coverage is dropped.

- Mitigation efforts to reduce the carbon footprint of buildings—both their construction and their operation—are well underway. They vary tremendously—by jurisdiction, by owner and by type of property. In general, serious mitigation is found more frequently in new commercial construction, leaving most of the built environment—both residential and commercial buildings—in catch-up mode.

- Adaptation efforts are also well underway. These are vitally important, because climate scientists tell us that even if society could achieve a drastic drop in GHG emissions, more volatile weather is almost certainly already here to stay. Adaptation efforts can also be expensive and not every owner or jurisdiction will be able to afford them.

- In the midst of all this change in the risk profile facing real estate, a data science revolution is going on. There is a gap between the large-scale weather models produced by NOAA and members of the AMS, and the risk analysis needs of the market. Put simply, the need is for micro-analysis of specific locations and different kinds of structures. Data vendors and consulting firms are innovating and putting out new products to meet the demand. Research done by the Urban Land Institute shows how this is a relatively new industry, with many of the unknowns associated with the launch of any forecast model.

- Large, well-financed property owners, and many of the world’s largest and wealthiest cities, are already deep into the process of assessing their climate risks and trying to figure out what to do about them. Organizations like the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the Federal Reserve are also ramping up their requirements for climate risk disclosures. There is a race going on—to see whether voluntary private sector efforts or government-led regulators are better suited to addressing both mitigation and adaptation challenges.

- Whatever side of this public-private divide you fall on, there can be no doubt that climate change raises challenges unlike any experienced in the world before. The temporal and geographic reach of climate risk is unprecedented in the history of humankind. It affects many more realms of human endeavor and the natural world than any prior policy challenge. The built environment is an important place to start tackling these challenges and growing our understanding of what it will take to address mitigation and adaptation simultaneously. Buildings are tangible and right in front of us. We live and work in them every day. We depend on them for leisure, for trade, for culture, and for industry.

An acknowledgment that real estate is an important part of the climate change puzzle is not without controversy. Some real estate owners say that it’s up to the tenants, not landlords, to change behavior. Transitioning to sustainable energy can compete with other worthy goals—like bringing down the cost of housing or making cities affordable for all kinds of businesses and manufacturing. Some of the most in-demand types of properties—like data centers and life science buildings—consume enormous amounts of energy. And, the developed world still has to reckon with the claims of emerging markets that they should be compensated for their mitigation and adaptation efforts. Yet, as difficult as these problems are, there can be no doubt that real estate construction and operations have to change from “business as usual.” Real estate contributes one third of GHG emissions, globally. In the world’s major cities it contributes close to 70% of all GHG emissions in these metro areas. Alongside other basic economic sectors—including transportation, agriculture, and manufacturing—real estate must re-assess its role in society and how it can be a net contributor to decarbonization instead of a net contributor to global warming.

Photo at top: Buildings on a Boston waterfront. Photo by Kristin Vogt on Pexels.