The New Zealand MetService’s chief forecaster Peter Kreft writes:

Getting the message out about severe weather, particularly when it involves rapid changes, requires excellent communication with the New Zealand public and many organisations managing weather-related risks. The message needs to be relevant and clear – not always an easy task, given that users of weather information have such diverse needs….In some ways, the challenge of getting the communication right is even more difficult than getting the meteorology right.

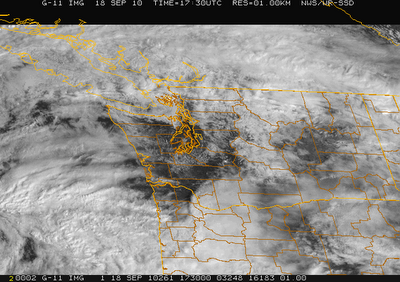

After recent events in New Zealand, Kreft should know. For days, the MetService had been tracking developing conditions for severe weather for parts of New Zealand. Then, on Wednesday, September 15, forecasters actually issued an advisory for gale force winds and “bitterly cold” weather several days ahead.

That’s when the other part of forecasting–the tough part- started to go awry. The media made references to a “massive” storm the size of Australia about to go medieval on New Zealand. References to civil defense authorities making preparations for the worst also hyped up the alarm.

[S]hortly after the MetService press release on Wednesday, this communication process was thrown off kilter by a media article about “the largest storm on the planet”. The article was based in part on the MetService press release but included information from other sources as well as a measure of journalistic licence.

Not surprisingly, weather discussion boards, blogs, and more media went haywire. Kreft says the misconstrued warnings went “viral”:

Within a matter of hours, MetService was fielding calls from people concerned about the “massive storm heading for New Zealand” and asking for clarification on various statements that MetService had apparently made. It was clear early on that people were confused about the source of the information they were receiving, and had been misled into thinking that the whole country was in for serious weather.

Not only worried citizens and nervous farmers but even disaster-preparedness authorities got caught in the storm of “mediarology.”

Unfortunately, MetService’s ability to get weather information to those who really needed to know was significantly hampered by media articles over-stating the area affected by the storm.

While severe conditions indeed occurred, the weather, as meteorologists had expected, was not bad everywhere in New Zealand

…leaving many people wondering what all the fuss was about. The danger this raises is that some of those may simply ignore the next Severe Weather Warning they receive.

All in all, it was a good reminder for why the weather enterprise continually needs to foster the partnership between scientists and the media, and ultimately the communication between forecasters and the public.