The Minnesota Vikings are hosting football outdoors for the first time in 29 years in their hometown, thanks to the collapse last week of the fabric roof of their home, the Metrodome. Last Sunday the football team decamped to a dome in Detroit, but tonight they’re expecting six inches of snow in Minneapolis to greet the Chicago Bears (themselves no strangers to snow and cold, of course).

The weather story this time is not just the falling snow, but the valiant efforts of workers and volunteers who have prepared the University of Minnesota’s FieldTurf synthetic field for this Monday night game. Not only does the snow need to be cleared, but the frozen field needs to be warmed sufficiently to prevent a slew of injuries. One player called the surface “hard as concrete.” Unlike NFL stadiums, which deal with a season that stretches into December, the university’s field is normally shut down by now, and does not have heating coils underneath to blunt the effects of freezing air temperatures. In addition the stadium as a whole was “winterized,” or put in cold storage with pipes dissembled to withstand freezing, so reawakening the facility for the game was quite a process.

The conditions of the game make one appreciate the need for a dome for winter sports in Minnesota, but last week’s spectacular roof collapse raises the architectural question: how to design a large roof for Minnesota’s famously varied climate.

The keepers of the Metrodome have good reason to believe that, an occasional roof collapse aside, fabric is still the right answer. The extremes of temperature in Minneapolis stretch and contract any covering, so in fact a flexible roof is ideal. And the maintenance of a fixed structure also means significant snow removal costs which may outweigh the occasional rip and fix for a fabric roof. (Thanks to the forecasts for heavy snow, workers were on the Metrodome roof trying to clear and melt snow last Friday before retreating in a lost cause .) The main downside of fabrics these days is the energy cost of the air pressure between the two sheets of the dome to keep the roof inflated.

Here’s a radio press conference discussing the climatic considerations of the stadium after a previous collapse of the Metrodome roof, also due to snowfall, back in 1982.

It takes a particular kind of storm to damage the roof. The design calls for warm air forced between the outer and inner layers to help melt the snow, but particularly cold storms can overcome that defense, especially if coupled with sufficient water content for a heavy accumulation and winds to drift the snow and cause particularly devastating loads in particular spots on the dome. Apparently even in Minnesota this doesn’t happen often enough to make other roof solutions less expensive or more convenient.

Jeff

Jeff

A New Way to Brighten AMS Meetings

Upon former Executive Director Ken Spengler’s death this summer, Andy White commented in The Front Page, “Ken made me feel like the most important member of the Society. I soon noticed he was that way with everyone.” Added John Lanicci, “The AMS is a lot like a close-knit family, and a much of that credit goes to Ken Spengler for his leadership, and always making you feel welcome, whether you were a newcomer like I was, or a member for 20 or 30 years.”

The AMS Beacons Program, a new initiative of the Membership Committee, is designed to carry on this special legacy of Dr. Spengler’s, fostering the AMS as an open, inclusive, and welcoming organization. The Beacons program is an ambassador program with a “member-staffed goodwill team” reflecting AMS’ initiatives to serve its existing, returning, and potentially new members. AMS Beacons will serve the AMS Executive Director and assist with Society and membership-related functions as deemed necessary or appropriate at AMS annual, specialty, and local chapter meetings and other functions.

The word “beacon” is defined as “a source of light or other signal for guidance; a source of light or inspiration.” This is what the Beacons aim to be for those who participate in the Society’s activities.

The 91st AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle, Washington, will be the “pilot” effort of the Beacons program. Beacons will be a friendly face, providing assistance and help to attendees–from the first time attendee who needs directions, to a regular attendee who might need some timely and thoughtful advice.

Beacons will have a significant presence at the New Attendee Briefing on Sunday, will be stationed at key locations (e.g., registration area, entryways, meetings with large gatherings, etc.), and informally greet and assist as they move throughout the venue during the week. As a volunteer, complementary resource to the AMS staff, Beacons will be trained on what questions and information should be referred to AMS staff members.

Watch for signs at the meeting, and posts on this blog, AMS Facebook and Twitter (#91stAMS) feeds for more about the role of Beacons.

Competing for Climate's Sake

Secretary of Energy Steven Chu says that Americans are having a new “Sputnik” moment. Now that China is moving full speed ahead to develop clean energy and mass transit, he predicts Americans will wake up to an economic and public relations challenge akin to the one that launched the space race with the Soviet Union more than 50 years ago.

You can watch the full speech given Monday at the National Press Club in Washington, D.C. As an Energy and Climate policy statement, Chu’s speech (see also the pdf or ppt versions at DOE) calls for vastly expanded federal funding to bolster American capabilities in engineering and science to seize the economic edge that clean energy will presumably provide in the coming decades.

Meanwhile, at the White House, as part of this energy policy push on Monday, the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology released its “Report to the President on Accelerating the Pace of Change in Energy Technologies Through an Integrated Federal Energy Policy.” In addition to economic and security rationales, the report calls for coordinated Federal energy policy in part to “mitigate the risk of climate change.” For this purpose,

the invention, translation, adoption, and diffusion of clean energy technologies need to occur within one to two decades, not the 50 years characteristic of major energy systems.

The report is sparse on details that relate directly to meteorological, oceanographic, and hydrologic aspects of renewables that currently occupy so many in the AMS community. In fact, even the frosted cupcakes served to speakers at the Press Club for Chu’s announcement were more weather-centric: there were atoms (go nuclear), suns (go solar) and….lightning (go thunderstorm power??).

Anyway, the larger political context is clear. The science community is swept along by geopolitics. It may take considerations of economic competitiveness and national security to get environmental well-being and risks onto a national, long-term agenda.

Why We Need Public Education in Earth Science

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director.

From the AMS project, Living on the Real World

Early in the Bush administration, sometime during the winter of 2001-2002, I got to sit in on a remarkable conversation. Three of us were meeting with the president’s new science advisor, John H. “Jack” Marburger, III, in his office. He was just getting his feet on the ground, and reaching out to different sectors of the science community. We were there to speak a bit to the contributions atmospheric science had made to the country, and how these contributions would not have been possible without steady government support, sustained for several decades. We weren’t there to ask for something; we were there to express thanks for past support, from both Republican and Democratic administrations.

At one point Jack invited us to each say something about the work of our respective organizations. I’d been at the American Meteorological Society only a year or so, and felt I’d rather say something about the work of our Education Program rather than my own policy interests. So I described how Ira Geer and his staff had constructed a wonderful Ponzi or pyramid scheme. Many science education programs focused on getting practicing scientists in the classroom; the idea has been that somehow these scientists could convey the excitement of the research bench. Some university faculty have proved better at this than others, but the results have been checkered at best. Ira and the AMS came at this from the opposite direction: public school teachers knew how to relate to the school kids; so why not give these teachers the resources they’d need to teach Earth science content? The AMS focused on reaching into the classrooms of education departments at universities and community colleges. They also chose to work closely, over a period of years, with a small cohort of public school teachers, who in turn would return home each year, and establish and maintain further cohorts (of cohorts) in their home states. In this way, Ira, his successor Jim Brey, and their staff of ten or so have reached 100,000 teachers and ten million students. Good numbers!

Marburger thought so too. He had been polite all along, but now grew animated, leaned forward. “American kids care about three kinds of science,” he said, “space, dinosaurs, and the weather.” He then recounted a story from his Brookhaven National Laboratory days. “We had an open house every year,” he said.

“One year, looking for ways to boost public attendance, we realized we had a National Weather Service Forecast Office on our [extensive] Brookhaven premises. We added them to our open house. The good news was that attendance shot way up! The bad news was everyone flocked to the Doppler radar. No one wanted to see our particle accelerators.”

What does this say? Public education in the Earth sciences provides the United States a badly-needed twofer. First, if educational statistics are leading indicators of the future place of the United States in the world, then our slippage relative to other countries in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) education augurs poorly. More emphasis on Earth science education offers a way out of our dilemma. As kids are drawn into Earth science, they quickly realize they need to learn a little physics, a little chemistry, a little biology – and top it all off with some mathematics. That childhood fascination with snowflakes and winter storms; thunder and lightning, downpours, and rainbows; with hurricanes and tornados? Earth sciences tap into this. They are a portal, a doorway, inviting kids into the world of science and technology more broadly.

Second, these school kids, when they reach adulthood, are going to be consulted frequently, through polling, through the voting booth, through their daily viewing choices on television or websites about their environmental preferences. What do they want their elected officials and leaders to decide and do relative to resource use, environmental protection, land use, building codes, preservation of habitat and biodiversity? High school may be the last chance to many to obtain the educational grounding they’ll need to make wise choices.

Sadly, most state educational standards struggle to include Earth sciences in any robust way. The tendency is for Earth sciences to be crowded out by physics, chemistry, biology, and mathematics. Understandable! These subjects are basic – they offer great employment opportunities going forward, and many of the same political challenges. But ideally, educators would use Earth sciences curricula as bookends in the secondary schools. The Earth sciences should be introduced at some point in middle school, to motivate students to learn the science and mathematics that are coming through the rest of the high school years. But then it should be re-offered, at a greater level of complexity and thoroughness in the senior year, when students can see how the physics, chemistry, and biology that they’ve been learning come together in order to explain how the atmosphere, oceans, and land surface work.

Easier said than done? Absolutely. But worth it if we hope to sustain our quality of life on the real world.

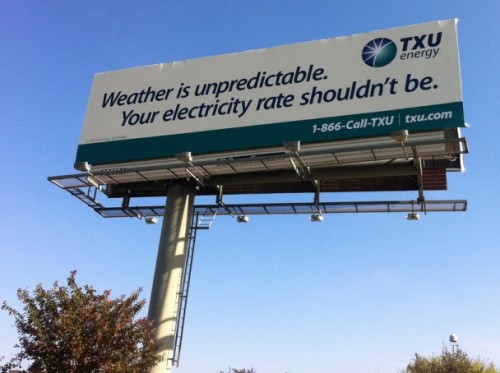

Roadside Detraction

Broadcast meteorologist Kevin Selle posted this picture to his blog, Digital Meteorologist, with the spot-on comment: “Note to self. Switch energy providers.”

Broadcast meteorologist Kevin Selle posted this picture to his blog, Digital Meteorologist, with the spot-on comment: “Note to self. Switch energy providers.”

Consider these events from the upcoming AMS Annual Meeting:

- What Do Meteorologists Need to Know about the Energy Sector–and Vice Versa–to Integrate Weather-Driven Renewables into the Electric Grid (Monday 24 January, 7 p.m., Town Hall meeting)

- Dollars and Cents: Weather for Energy Markets and Weather Fundamentals for Energy Planning (Thursday 27 January sessions of the Conference on Weather Climate and the New Energy Economy).

Meanwhile the atmospheric science community moves on, working to make lives easier and more stable for utilities and their customers. For instance, Erica Zell will be presenting “NASA Products to Enhance Energy Utility Load Forecasting” (Wednesday, 26 January) in Seattle. She notes:

Existing load forecasting tools rely upon historical load and weather, and forecasted weather to predict load within energy utility service areas. Microclimates and weather events such as stalled fronts have proved particularly challenging for load forecasting. The shortcomings of load forecasts are often the result of weather data that is not at a fine enough spatial resolution to capture local-scale weather events.

Zell offers hope by integrating high resolution satellite-derived atmospheric information into load forecast tools.

We could go on, of course.

Energy provider driving down Texas highway mutters: “Note to self. Switch energy providers!”

Pioneering Space Weather Expert Dies

Paul Kintner, a Cornell University engineering professor and head of the university’s Global Positioning Systems Laboratory, died Monday at age 64. He’d been battling pancreatic cancer.

Kintner was a major influence in the engineering world for recognizing the potential of global positioning technology, but to the AMS community he was a leader in the science of the effects of the Sun on the atmosphere, starting from his Ph.D. work at the University of Minnesota on the plasma physics of the northern lights high above the Earth. Later he studied the effects of the Sun on radio signals and in particular GPS. His observational studies made him the discoverer of “electrostatic ion cyclotron waves, double layers and lower hybrid solitary” in space.

Says Rich Behnke of NSF, a member of the AMS Committee on Space Weather,

Paul was the quintessential professor – super bright, outspoken, a superb scientist and a deeply committed teacher. He has been a real pioneer in developing GPS technology and advocating the importance of space weather on society. He was also a personal friend, a running buddy, and a wonderfully warm human being with a great smile.

Kintner was scheduled to be one of the featured speakers at the upcoming Symposium on Space Weather at the AMS Annual Meeting in Seattle in January. His topic during the Tuesday, 25 January session was to be “GNSS, GPS, Modernized Signals and the Next Solar Maximum.” In his abstract he notes that GPS had just become open to widespread application during the previous solar max, which at one point in October 2000 resulted in a 26-hour outage of navigational services. Now many more applications are based on GPS and a solar max is approaching in 2013. While newer, more robust technology is being phased in, Kintner noted that

the overwhelming majority of operational GPS receivers will use the legacy GPS signals during the next solar maximum….[Precision applications based on GPS] have dramatically increased over the past solar minimum along with the assumption that the services will be truly uninterrupted and continuous. Providers of these services should be aware of three potential space weather impacts, density gradients as before, scintillation and especially phase scintillation which has only recently been resolved, and solar radio bursts about which we know little.

This presentation at the meeting will be replaced by a tribute to the Kintner and his pioneering contributions to our sciences.

You Weren't the Only One Who Mist This Game

Football is tough enough to play when the visibility is good; when you can’t see your own teammates, it’s a whole lot tougher.

In the infamous “Fog Bowl” on 31 December 1988, the Philadelphia Eagles somehow managed over 400 yards of passing. Then again, the game started out sunny and unseasonably warm, perfect for the Eagles’ flashy offense. But thick fog soon rolled in off the lake and onto Chicago’s Soldier Field until visibility was less than 20 yards, making passing a precarious proposition and helping the defensive minded Bears grind out a 20-12 victory with their strong ground-based attack.

Last Friday two Michigan high school football teams topped that NFL classic with an even thicker fog-bound playoff game of their own. At least, it looks like they did…through practically no one actually saw what was happening on the field. Rub your eyes, clean your computer screen, and check out the video highlights here.

Host Bedford-Temperance High School built a two-touchdown edge over Grosse Pointe South High School under the Friday night lights, but gave the ball away four times and saw their lead evaporate in a series of miscues. Twice the Grosse Pointe defense scooped up fumbles and returned them for touchdowns when the Bedford-Temperance quarterback couldn’t find the teammate he was supposed to hand off to in the mists.

The game came down to a last-second Grosse Pointe kick that, according to the referees, split the uprights for a 44-42 victory over Bedford-Temperance. This was one game where the guys in the striped shirts really were the only people in the stadium in a position to know for sure.

A White House Moment

Yesterday at the East Room of the White House, President Obama honored the winners of the National Medal of Science, including AMS past president Warren Washington. President Obama noted:

It’s no exaggeration to say that the scientists and innovators in this room have saved lives, improved our health and well-being, helped unleash whole new industries and millions of jobs, transformed the way we work and learn and communicate. And this incredible contribution serves as proof not only of their incredible creativity and skill but of the promise of science itself.

For more on the award, see our post from October 16.

On the Road Again!

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director. From the AMS project, Living on the Real World

The meetings and discussions will be of interest in and of themselves. In some areas of our lives, weather is vital, but we can do little more than sigh. Give a

farmer thirty minutes notice of a coming hailstorm? He’s going to lose his wheat crop anyway; he can just start the grieving process half an hour sooner. In other venues, we’ve got plenty of weather information, but we’ve made it less relevant. That’s why offices are housed in buildings… and why we have domed football stadiums.

But roadways are an intersection (forgive me…too tempting!) where (1) weather affects safety and the economy, and where (2) those affected – the drivers, the traffic managers, the roadway maintenance folks, the businesses dependent on supply lines fed by road – if given the right information in the right way, can actually do something about it. A hailstorm is coming? Traffic managers can put out the word; drivers in the hailstorm’s path can divert or stand down until the hazard passes. Snow is on the way? We can get out the trucks with the plows and salt. And people are using the roadways to get from home to the office, or to that football game, aren’t they? Even in this age of virtual connectivity, physical connection still matters, commercially and socially, and much of that connection is made by roadway.

So road weather is a very special topic, rich with potential for improving the human condition.

We also find road weather to be an interesting example – a microcosm, if you will – of policy issues that play across what appears at first blush to be a “stovepiped” landscape. But let’s probe a little deeper. In this instance, we find leaders who see their institutions as the organ pipes they are, and are jamming, playing a little music together (to build on yesterday’s metaphor from my post, “Stovepipes! The Musical“). They’re effectively working across boundaries – boundaries separating::

Federal agencies. The DoC/NOAA/National Weather Service and the DoT/Federal Highway Administration each have a piece of the puzzle, don’t they? To be valuable, weather information must be applied. As the FHWA tries to make road travel and commerce safer and more efficient, it must integrate weather with traffic conditions, road maintenance, and other elements of the mix. To be useful, the agencies need each other! At the policy forum, they’ll be signing an memorandum of understanding (MOU) – a policy document – committing to another five years’ collaboration on road weather research and services.

And by the way, there are policy interfaces within each of those two Cabinet-level Departments, aren’t there? FHWA is competing with its rather larger sister agency, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Federal Railroad Administration, the Maritime Administration (MARAD), and many more, for attention at the top. NWS is always trying to make sure

Science Policy: What Would the Founding Fathers Do?

by William Hooke, AMS Policy Program Director. From the AMS project, Living on the Real World

“Facts are stubborn things, but statistics are more pliable.”

– Mark Twain

When I was a graduate student in physics at The University of Chicago, the department had a weekly seminar. One year Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar, a faculty member, already a famous astrophysicist (he would go on to win the Nobel prize) and author of over 1000 publications, delivered a talk on his new theory of quasars. The next week’s speaker happened to be Tommy Gold, a Brit, a fellow of the Royal Society, and then on the faculty at Cornell. He laid out a competing theory. When Gold was done, Chandrasekhar was the first person to ask a question. Wearing his signature pinstripe suit and looking like he just stepped out of the pages of GQ, Chandrasekhar cut a dignified figure as he rose from his chair. “Surely you would agree…” he smoothly began…

Can’t remember exactly what he said next, but it was the equivalent of asking Gold whether he believed that 2+2=4. It was also the first step down a line of argument that would lead to Chandrasekhar’s theory. The room was packed, but you could have heard a pin drop. Gold looked at him for what seemed like forever; then finally said “No.”

Maybe for the more senior faculty this was just another day at the lab, but we students had never seen a scientist do that. Every person in the room knew the only right answer was “yes.” Most of us had also been present the week before. Chandrasekhar glowered, then silently took his seat. A serious chill set in the room. The Q&A went on for some time, but never fully recovered.

Tommy Gold knew that you couldn’t separate data and facts from considerations of the end. To defend his theory he was going to have to say “no” at some point, so he might as well do it early.

It was not science’s best day. But in that instant I took to heart – internalized in my gut, not just my head – that while science might be objective, the pursuit of science could be very political – and combative. As a result, the process of collecting and analyzing the data can’t really be separated from considerations of the end use.

I got to see this up close and personal from 1987-1993 . At that time I was the NOAA Deputy Chief Scientist. The National Acid Precipitation Assessment Program (NAPAP) Program, an interagency group, was administratively housed in NOAA under the leadership of the Chief Scientist. The same argument was playing out, but now