by J. Marshall Shepherd, AMS President. The full text was posted earlier today on his blog, Still Here and Thinking.

This week NOAA, the parent agency for the National Weather Service (NWS), announced a hiring freeze at a time when its vacancy rate is already around 10%. I understand that this number is near 20% for the Washington, D.C. area NWS Office. At this point, pause and consider public safety. As we enter the severe weather/tornado season, the Sequester has forced the hand of our NOAA management and possibly jeopardized the American public’s safety, stifled scientific capacity, obliterated morale within NOAA/NWS, and dampened hopes for the next generation of federal meteorological workforce. Beyond safety, we have increasingly clear evidence that weather is important to our economy, a critical consideration for an agency in the Department of Commerce.

Now to be clear, I know, personally, the senior level managers at NOAA/NWS very well: they will do everything within their power to adjust and mitigate impact. This commentary is really not about them.

Like our dedicated military, border patrol agents, police officers, and firefighters, NOAA employees provide a valuable public service that affects our lives every day, including warnings and alerts. A community would be outraged at cuts to a nearby Fire Station staff, particularly during a rash of arsons. Additionally, NOAA/NWS personnel are increasingly missing as subject matter experts for major Emergency Management training and conferences.

The vibrant and critical private weather enterprise adds value to data, models, and warnings from NWS. I have often joked that NOAA is to the private sector weather enterprise, what the potato farmer is to a company that makes French fries. It is a vital partnership, which includes research and applications from academic partners as well. The AMS Washington Forum will bring together these sectors for a vital meeting next week, including the increasingly important discussion about creation of a U.S. Weather Commission.

I am fearful of what is happening in our community with draconian sequester cuts, challenges to travel/science meeting attendance and other stresses on science/R&D support within NOAA, including journal publications, fees, etc. If you couple this with looming concerns about weather satellite gaps, computing capacity to support advanced modeling, and employee morale, we are slipping down a slippery slope of “eroding” the U.S. federal weather enterprise. Since industry, academia, and federal agencies work closely together, these effects will ripple throughout the broader community.

The public may take for granted a tornado warning based on Doppler radar or a hurricane forecast based on satellite information. Likewise, the public probably just assumes that they will have 5-9 day warning for storms like Sandy; 15-60 minutes lead time for tornadic storms approaching their home; weather data for safe air travel; or reliable information to avoid hazardous weather threatening military missions. However, these capabilities can and will degrade if we cut weather balloon launches, cut investments in the latest computers for modeling, reduce radar maintenance, delay satellite launches, or shatter employee morale. We are accustomed to progress and innovation, but I fear capabilities will regress instead, jeopardizing our lives, property, and security. And I have not even spoken about the challenges that a changing climate adds to the weather mix.

At my university, I see young, vibrant, and talented students everyday who embody the next generation weather enterprise. They are taking notice of what is happening, and I believe this seriously jeopardizes our future workforce.

As we enter the active spring tornado season, let’s hope the sequester season ends, before the hurricane season begins.

Jeff

Jeff

For Science and Discovery, Videoconferencing Won't Get It

by J. Marshall Shepherd, AMS President. The full text was posted earlier today on his blog, Still Here and Thinking.

I am sitting here during coffee break at the NASA Precipitation Science Team Meeting in Annapolis, Maryland. This meeting is a gathering of the world’s top scientists working with the TRMM, GPM, and other NASA programs related to precipitation, weather, climate, and hydrology.

A prevailing lament of many of my federal colleagues attending this meeting is the concern about the ability to attend scientific meetings because of travel restrictions and sequestration/budget issues. As I ponder their laments, I reflect on whether (1) these colleagues are spoiled federal employees not adjusting to austere budgets, (2) these colleagues are victims of a perception about federal employee travel because of a few isolated bad choices (e.g. GSA conference story publicized in the media, or (3) I have a bias as AMS president because we host meetings and have an interest at stake.

Here are four things that I come up with:

We risk stifling scientific and technological innovation: Yes, budgets are tight and some travel/conference activities (a very small percentage) are questionable. However, as someone that has attended scientific meetings and conferences for over two decades, these meetings are very intense, intellectually-stimulating, and advance the science. They are not vacations or frivolous. I arrived at the meeting room yesterday at 7:45 am, sat through various sessions, met with two different working groups/planning committees, and discussed a potential new scientific collaboration. I got to dinner at 8:15 p.m. There is a movement towards the use of various videoconferencing solutions. Those advocating these measures have completely missed the point that the most valued aspects of attending conferences and meetings are the “hallway” meetings, poster sessions, lunch/dinner meetings that lead to potentially transformative research, or the chances to caucus with colleagues on a new method or technology. (AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter made these points in The Front Page in December.) The presentations (what gets videoconferenced) are important but often secondary or tertiary to the value of such meetings.

All professions stay current on their topic, why should scientists and engineers be different?: I cannot imagine any profession or industry not wanting its employees to be current on the latest methods, techniques, and discussions. I am certain that leading companies continuously train their employees. Scientific meetings are “the training” for many professionals. For example, our AMS annual meeting has up to 20+ “conferences” within one conference. It also has various short-courses, town halls, and briefings. I argue that we risk “dumbing down” our U.S .scientific workforce with such arcane travel restrictions. At a time when we need to push the innovation envelope for society, we risk folding it up and discarding it. As an example, our Air Force pilots are the best in the world. They develop their skills through course work and flight simulators. However, at some point, they have to get into a real aircraft and interact with other pilots to gain knowledge, experience, and “tricks” of the trade.

Another offshoot of federal travel restrictions is our standing with the international community. U.S. presence is essential at many international meetings. Many of our collaborators and colleagues abroad are also being affected in terms of their own meeting planning, expectations, and the possibility of no U.S. presence. Does anyone see the inherent problem with this from the standpoint of international partnerships and our reputation?

What I also find amazing (and admirable) is that many federal colleagues (often called “lazy” or not-dedicated) have paid their own way to meetings or conferences. But if they do this, are they representing themselves? Should they discuss their work at the conference (since technically they are on vacation)?

Stifling the Private Sector: The private sector and small businesses are critical to our economy. I spoke with several major company representatives and small businesses at our 2013 Austin AMS meeting. They were also lamenting. They were talking about how the lack of federal attendees severely hinders their access to potential new clients and business. This has more than a trickle down effect on the health and vibrancy of our private sector and its contributions to economic vitality.

The Next Generation: As a young meteorology student at Florida State, I was in awe of attending the AMS and other meetings and having the opportunity to meet the woman who wrote my textbook, the Director of the National Hurricane Center, or a NASA satellite scientist. Our current generation of students (undergraduate or graduate) are in jeopardy of losing these valuable career-enriching opportunities. AMS, for example, hosts a Student Conference and an Early Career Professional Conference. By design, we expose hundreds of future scholars, scientists, and leaders to the top professionals in our field. In 2013, many of these professionals can’t travel or have to jump through hoops to declare the travel “mission critical” in NASA-speak (I spent 12 years as a NASA scientist).

I conclude that I am not being a “homer” on this issue. There are real concerns about the status and future of scientific discovery, innovation, private industry health, international reputation, professional development of our workforce, and exposure of our next generation.

Video conferencing just won’t get it.

Added 29 March, to clarify: I am aware of the challenges related to travel and emissions. Three points are worth adding:

- AMS has a Green Meetings initiatives.

- Large shifts to videoconferencing are not completely immune to costs, such as energy required to support increased computing/IT requirements, and

- Videoconferencing may be highly appropriate for smaller committee and board meetings but not large scientific meetings, which was the point of this post.

AMS Policy Colloquium: Where Science, Policy, and Communication Collide

by Jen Henderson, Skywarn storm spotter, writer, and grad student at Virginia Tech in Science and Technology Studies. Republished from her blog at JenHenderson.com

This week, I’d like to have a little chat with my friends and colleagues who are connected to the world of atmospheric and meteorological sciences: Faculty members, industry professionals, employees of NOAA and the National Weather Service (NWS). And yes, this includes my fellow graduate students in these fields, as well.

Here’s a little story:

Last week, as I sat in front of a computer at a local NWS office,  I found myself mesmerized by the most simple of objects: a weather balloon.

I found myself mesmerized by the most simple of objects: a weather balloon.

In the photograph in front of me, a meteorologist stood dressed in a warm jacket, jeans, and hat gripping a thin cotton string topped by a whitish orb. It hovered like a small sun over his left shoulder. I recalled the time I watched a weather balloon launch a few months ago, how carefully the meteorologist measured the helium that inflated the balloon, which before it filled with air sat on the table like a large loaf of bread dough. I helped him inspect it for defects before following him out into the dusk of an early autumn evening where he released it into the cloudy sky above. He would later tell me that launching the balloon, and the small brick-like rawinsonde that dangled below on its journey into the upper atmosphere, was still one of the most reliable means for collecting data important to weather forecasting.

My question that day was how to get members of different publics as excited about weather as I then felt. What kind of research were meteorologists able to do based on this weather balloon launch, or sounding? What did the launch reveal about trends in weather? Where might people like me, a graduate student in a discipline outside the sciences, learn more?

- What I really want to know was this: How might meteorologists and atmospheric scientists more successfully communicate what they do to those of us who are not familiar with their work? How might they channel the passion they have for what they do into stories that inspire the rest of us?

Communicating sciences to various publics has been on my mind for several years, but it was brought home to me last summer when I attended the American Meteorological Society’s annual Policy Colloquium in Washington, D.C. I was one of a few social scientists to mingle with and learn from various atmospheric and meteorological scientists, ranging in experience from graduate school students to tenured professors and industry professionals. While the colloquium centered on introducing attendees to several aspects of the policy world, which is rich in opportunities and complexity, the underlying theme, you might say, focused on encouraging scientists to think about their potential role in communicating what they do to different publics–policy makers, elected officials, students, and members of the general public.

As I listened to seasoned speakers from all walks of life, I gained a few unexpected insights into science policy and scientists themselves.

- Many scientists harbor the assumption that they’re not good at communicating their work. Not true! I heard many of my scientist colleagues refer to themselves as bad communicators, introverts, and pointy-headed thinkers. They insisted they didn’t know how to communicate (although they did have an inkling about how important it is that they do so). What I experienced instead was the opposite. Most of the participants were excellent story tellers and more than adequate communicators, they just hadn’t thought about the intersection of their narrative and research skills. With a little practice (and a lot of critique), many left the colloquium more confident about their ability to explain not only their work but why it might be important to different audiences.

- Science affects policy and policy affects science. In fact, I would suggest that the two are intertwined in ways that make it difficult to distinguish them at times. Issues surrounding funding, regulation, and accountability shape the types of science we do and the ways in which it gets done. And then of course the types of science performed across the country affect and influence policy. See how they’re intertwined? There is no pure science nor is there pure policy. As they say in my discipline, Science and Technology Studies, they are co-constructed.

AMS policy group at Mount Vernon. - There are multiple ways to participate in communicating sciences to your chosen public. With the help of communications staff members from The American Geophysical Union (AGU), we practiced distilling lengthy research agendas into a few sentences that could resonate with a listener. AGU staff encouraged us to think about the story of our research, the narrative hook that would capture someone’s interest; to practice talking about our research with school children, members of the media, even through socia media sites; and to consider building a relationship with our local government officials, many of whom have little scientific background but must make decisions involving scientific information. (For a concise way of thinking about how scientists can act in multiple ways, read The Honest Broker, by Roger Pielke, Jr., or check out his awesome blog.)*

So what’s my overall message?

You, my friends, have the opportunity to join an amazing group of people at the American Meteorological Society who believe that the passion each of you feel about your work can be productively channeled into the science policy world…and beyond. The same elements of the universe that inspire you to pursue your research can inspire others. Your experience can give you a voice in shaping the multiple conversations among members of the public, policy makers, industry professionals, local government officials, and your fellow colleagues.

I wish I could attend again. The colloquium opened up opportunities and allowed me to make connections I wouldn’t have had otherwise. It helped me understand the challenges of the political world and how these issues shape my own work. And it was so much fun!

The AMS Policy Colloquium is now accepting applications for the next cohort who will meet in DC for nine days this June. But hurry, the deadline is March 31. If you’re a student or faculty member and you’re accepted, you can apply for NSF funding. So what have you got to lose?

*To read more about science policy, the AMS colloquium, and how these two things have shaped my work and my colleagues’ work, please check out our article in the February 19, 2013 issue of Eos, the AGU’s weekly newspaper. Goldner, Henderson, and Shieh.

AMS eBooks: No Longer Just Icing on the Cake

One of the growing traditions at the AMS Annual Meeting has been the cake cutting celebration of new books published by the Society. This year’s meeting was no exception—the ceremony touted a particularly yummy year of reading provided by AMS Books sweetened by a brand-new venture into electronic reading.

Indeed, the icing on the cake—literally—was the enhancement of the program’s eBook distribution. Written into the frosting was the impending collaboration between Springer and AMS to enable electronic distribution of dozens of books and monographs.

If you weren’t fortunate enough to get a slice back in January, hunger no longer: today, you can have your cake and eat it, too, because the Springer-AMS website is now officially open.

Springer’s Senior Publishing Editor in Earth Science and Geography, Robert Doe, says, “The AMS book program is internationally renowned, and many of their titles are classed as seminal. I am delighted that these quality books will now be available electronically for the very first time.”

The 12 titles available as eBooks immediately will grow to approximately 50 in 2013, and 3 to 5 of AMS’s selection of new releases will be added each year. The current collection includes key works on climate change and meteorological hazards including Lewis and Clark: Weather and Climate Data from the Expedition Journals and Deadly Season: Analysis of the 2011 Tornado Outbreaks aswell as instructional texts like Eloquent Science: A Practical Guide to Becoming a Better Writer, Speaker, and Atmospheric Scientist. Over time, the eBooks list will be expanded with out-of-print legacy titles that will also be available through print-on-demand.

The collaboration with the world’s largest collection of science, technology, and mathematics eBooks–enables AMS to benefit from Springer’s innovative ePublishing technologies, long-term library relationships, and reach into global institutional markets. According to AMS Executive Director Keith Seitter, “The American Meteorological Society is committed to achieving the broadest possible dissemination of the important science published in our books. This agreement with Springer opens new avenues for that dissemination and therefore represents an important means to achieve our goals.”

“Our arrangement enhances both discoverability and access to our content, but puts Springer in the driver’s seat in terms of remaining on top of technology—file formats and devices that tend to change as often as each year,” says AMS Books Managing Editor Sarah Jane Shangraw.

For individuals, AMS eBooks will be available for purchase not only from Springer but also eBooks.com, Google Books, and other eBook retailers in files downloadable to any device. People at institutions that subscribe to SpringerLink will be able to view web-based books using their institutional login. The SpringerLink “Springer Book Archive” will make available books published prior to 2005.

AMS will continue to distribute print books directly and through its print distribution partner, the University of Chicago Press.

A Simple Investment in the Sciences

It’s not every day you get a chance to invest in a sure-fire start-up based on science you know very well. Even rarer is a start-up that is the brainchild of a group of determined middle school students. And when was the last time you could make that investment, for free, with just a click on the internet?

Vicky Gorman, a science teacher in Memorial Middle School in Medford, New Jersey, is currently taking the AMS’s DataStreme Atmosphere distance learning course. The students, and the start-up venture, are hers, so we’ll let Vicky explain it as she did to AMS President Marshall Shepherd this week:

Two of my 7th grade students approached me last fall about submitting an idea for the $5000 Beneficial Foundation School Challenge. These two young ladies brought many ideas and wonderful enthusiasm to the table. We decided on a “Citizen Science Education Program” to bring science into the lives of the citizens of our community, and allow students to apply their science knowledge to the real world. I am developing this program with my students now as my final project for the DatasStreme course. The focus of the program is Earth Science, which as you know, needs a greater presence in both child and adult education in the 21st century. I can see this project making a difference in our community, county, state, and beyond.

Fast forward a few months to January of this year. We were selected as a top ten finalist! However, now, we need your help. We have posted a video to the Beneficial Challenge web site, as have the other nine schools. Click there and you will see that this final phase of the competition will be decided by number of votes for our video.Voting opened on Monday, and closes at midnight on next Monday, 11 March. You may vote every day and multiple times every day.

Here’s what you’re looking for when you click on the links above:

Let’s take this opportunity to start up something new, and invest in the future of earth sciences.

Vision Prize: Polling Experts about Climate–and Each Other

If you can’t get enough of prediction by forecasting weather or climate–or basketball tournament brackets, elections, and the Oscars—here’s the game for you: Try the web-based opinion poll of climate and earth scientists—the Vision Prize.

A nonpartisan research project using the Web for incentivized polling, the Vision Prize is testing a new way to get scientists to speak candidly to the public about climate change, without media filtering.

“We all recognize the need to do science communication, but we still seem to struggle to do this well,” says Jonathan Foley, Director of the University of Minnesota Institute on the Environment. “As a new approach to this problem, Vision Prize deserves our attention.”

Foley’s institute is collaborating with Carnegie Mellon University to try out this poll-based experimental method. The advisors include behavioral psychologists, economists, and public policy scholars, so participating scientists may feel a bit like the tables have been turned, with humans becoming the lab rats on the treadmills.

Don’t let that stop you, however. Participants are having fun at it, getting serious results, learning about their colleagues, and yes—there’s that “incentivized” part—they’re winning prizes, too. Participants not only make gut-check projections about future climate but also predict what their colleagues think—a way for the rest of us to gauge their confidence and consensus.

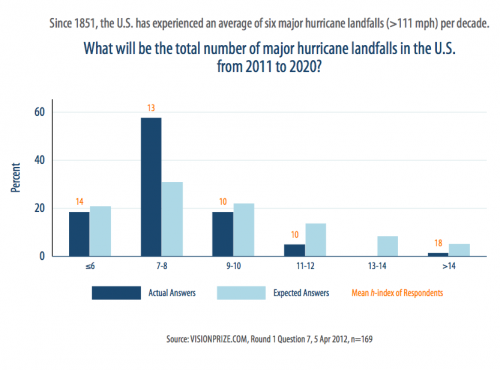

Surprisingly, so far the results show that experts systematically underestimate the consensus amongst their peers. For example:

(“Expected Answers” are predictions of what the most likely answers were; “Actual Answers” are predictions of climate made by those surveyed.) The participants who best predict their colleagues’ opinions win gift cards towards the charity of their choice. All in all, scientists should feel right at home doing public service to win a chance to do even more public service.

Poll results are annotated by a measure of the stature of the participants within the climate science community. The web site provides h-index scores that factor both how many papers participants have published and how often those papers are cited. In a press release today, Vision Prize noted that the polls have been taken by some impressive participants.

“We’re very encouraged by the high quality of our 275+ expert participants,” says Peter Kriss, the director of research. Vision Prize provides mean h-index scores to give readers of the poll an approximate metric for assessing the relative expertise of the participants who selected a given answer. “We were very impressed to find mean h = 36 among our top 50 experts,” says Kriss. As a point of reference, h ≈ 12 might be a typical value for advancement to tenure at major research universities; membership in the U.S. National Academy of Sciences may typically be associated with h ≈ 45 and higher (Hirsch, PNAS, 2005).

The mean for all participants so far is h=13, but that may change soon.Vision Prize is now actively seeking additional participants from the scientific community, including doctoral students. “The larger the number of climate and earth scientists participating, the more useful the results,” says Vision Prize Managing Director Mark Kriss.

Vision Prize makes its results open to the public, so it’s certainly imaginable that not only are policy makers and pundits paying attention but also some prediction obsessed spectators who themselves are predicting how the polls turn out. The web site is currently polling about a round of topics that began in September 2012 and will wrap up at midnight, April 30th.

If you qualify, by all means get into the game as a participant as soon as possible. Answering the survey questions takes about five minutes, after quick registration. Mark Kriss, Vision Prize managing director, says, “Early voting helps boost participation rates so your post would be timely now. The larger the number of participating scientists, the more useful the results.”

By the way, even if you don’t end up participating, the Vision Prize is also open to suggestions about questions to ask the experts.

The Short and Long of Sequestration Forecasts

By now your head is probably spinning with all the conflicting forecasts what the Federal sequestration will do to us. (For a sample, try the Washington Post’s compilation of various projections.) If the collective disagreement of pundits indicates a kind of chaos–a bit like making a weather forecast when the numerical models just will never converge, an ensemble gone haywire–then you’re right. The reason for the confusion, says AMS Policy Program Director William Hooke, is that nobody knows what will happen. Here’s how he put it, in an interview with The Weather Channel’s Maria LaRosa on yesterday’s Morning Rush show:

TWC: What should we expect in particular for weather agencies? What is your top concern right now?

My top concern is the same as the weather top concern. The uncertainty in all this. We make good weather forecasts because we have practice. The case of the sequestration is something different. It’s unprecedented. We don’t know what will happen. That includes the policy makers at the top and the bench forecasters at the bottom.

TWC It may be a couple weeks before we some of the direct impacts? How are you folks preparing, or can you?

Hooke: You know, an NGO like the American Meteorological Society can’t do much but watch with horrified fascination. The real issue is what happens to those scientists and technicians who try to keep the radars prepared and keep staff online when bad weather occurs with little notice, and just be ready to protect property and to protect the American public.

TWC And the AMS gives out grants for all kinds of things, and how does that impact money that you guys give out?

Hooke: We’ll certainly be getting less and so we’ll be less capable in turn. We, like many private sector firms and academic researchers, depend a great deal on NOAA, the National Weather Service, and other federal agencies to keep things humming, particularly innovation, particularly improvements in forecasts and services.

However, as we know from weather forecasting, the short term may be overwhelmed by chaos and uncertainty, but that doesn’t mean seasonal or climate projections can’t have some teeth in them. City College of New York physics professor Michael Lubell, who is also director of public relations for the American Physical Society, told Ira Flatow yesterday on National Public Radio’s Science Friday that the short term uncertainty is itself a determinant for the long term prospects of science:

One of the difficulties we have in science is that it’s not like a road project. You say, “well, we don’t have enough money to continue paving something today, we’ll call the crew off and bring them back six months or nine months from now.” Science—you cut it and the people aren’t coming back, facilities aren’t going to be opened again….

I think of this as taking a frog or taking a goose in a pot of water and we’re slowly heating it up, and eventually the goose gets cooked and by the time it gets cooked it’s too late to deal with it. That’s what’s going to happen to us. Unfortunately the public doesn’t see it immediately, and I think the President probably made a mistake by trying to scare people, because you’re not going to see it at least for several months, if not then. It’s just going to be a slow erosion, and the case with science, as I said, is that erosion is not some you see easily.

I would argue…that the more devastating effects are the long-term effects. If you have a longer line at the airport today, put money back in and those lines will get shorter. If we remove our money from the investment—and let me just make a couple comments about this. I mean half of the economic growth since World War II was attributable to science and technology. One fact that people usually don’t know is that laser enabled technology accounts for one-third of our economy today, and they began with a small amount of government money more than 50 years ago.

[With cuts] the programs shut down forever. When people are smart, they find other things to do.

State of the Union Address Sets Stage for Senate Climate Hearing Today

If, last night, you made it through the usual State of the Union appeals to bipartisanship, tax reform, health care, job creation, deficit control, and industrial revitalization–then you heard President Obama’s unusually blunt promise to take action on climate change.

And all you had to do was wait through the rest of the night before Congress started working on its response. The Senate Committee on Environment and Infrastructure, chaired by Senator Barbara Boxer, has already lined up a session on the “Latest Climate Science” for this morning, at 10 a.m. EST. The blue-ribbon panel of invited experts providing testimony includes AMS President J. Marshall Shepherd and you can follow the live webcast of the hearing at the committee’s website.

The hearing originally looked like a relatively routine overview of science following the release of the newly drafted National Climate Assessment, but now it is charged by the President’s new resolve to begin dealing with climate change, with or without Congressional input. His position was staked out in a few sentences hunkered down amidst a flurry of points about energy efficiency and independence:

[O]ver the last four years, our emissions of the dangerous carbon pollution that threatens our planet have actually fallen.

But for the sake of our children and our future, we must do more to combat climate change.

Now, it’s true that no single event makes a trend. But the fact is, the 12 hottest years on record have all come in the last 15. Heat waves, droughts, wildfires, floods, all are now more frequent and more intense. We can choose to believe that Superstorm Sandy, and the most severe drought in decades, and the worst wildfires some states have ever seen were all just a freak coincidence. Or we can choose to believe in the overwhelming judgment of science and act before it’s too late.

Now, the good news is, we can make meaningful progress on this issue while driving strong economic growth. I urge this Congress to get together, pursue a bipartisan, market-based solution to climate change, like the one John McCain and Joe Lieberman worked on together a few years ago.

If Congress won’t act soon to protect future generations, I will. I will direct..I will direct my cabinet to come up with executive actions we can take, now and in the future, to reduce pollution, prepare our communities for the consequences of climate change, and speed the transition to more sustainable sources of energy.

The threat of unilateral Executive action set off a storm of commentary (e.g., Exhibit 1, Exhibit 2) and is sure to put the Senate in a very different frame of mind for today’s hearing. As for the science of climate change and its impacts–the focus of the hearing–this morning’s line-up of guests undoubtedly will have plenty to say about the latest findings. For example, Prof. Donald Wuebbles of the University of Illinois, and Dr. John Balbus, of the National Institutes of Health, are among the lead authors of the 2013 National Climate Assessment (available for comment). Meanwhile, Dr. Shepherd has been speaking out frequently on both the impacts of climate change on society and on the scientific approach to evaluating the effects of climate change on extreme events, and of course he is part of the AMS Executive Council that updated the Society’s information statement on climate change in 2012.

25,000 Euros for Your Thoughts: The Harry Otten Prize

No longer is it enough to offer a penny for your thoughts. As a vital player in the meteorological enterprise, your creativity is now worth a whole lot more–to be exact, 25,000 Euros, if you win this year’s Harry Otten Prize for Innovation in Meteorology. The prize, which will be awarded every two years, was established with funds from Netherlands meteorologist/entrepreneur Harry Otten, president of MeteoGroup/Meteo Consult. The prize website explains,

A substantial part of the national gross product in many countries is weather dependent. National weather services and the private sector have been innovative for more than a century to make better use of our meteorological knowledge. However, large gains are still to be made and the prize encourages individuals and groups to come with ideas how meteorology in a practical way can further move society forward.

If you can get your application together (the online process is actually quite straightforward) by the 10 March 2013 deadline, you might end up being one of the select three finalists to present your ideas to the Otten Prize jury at the European Meteorological Society meeting in September 2013. The winner will be announced within a day of the final presentations.

To get more of an idea of how the prize process works–and how inflation has marked up the value of your ideas by 2,500,000%–The Front Page interviewed Harry Otten Prize board member Richard Anthes. Dr. Anthes, who is well known to our community as an AMS past president and the president emeritus of UCAR, graciously provided the following responses:

Front Page: What was Harry Otten’s hope for this prize? Why is the Harry Otten Prize a good thing for our community?

Anthes: Harry Otten wants to encourage people to think of innovative ideas that will contribute to or use the science and technology of meteorology to provide services or products that will benefit society. The Prize is good for our community because it stimulates us to think in creative new ways about how our science can be advanced and used in constructive ways.

In the past you’ve described this prize for Innovation in Meteorology as rewarding “clearly innovative contributions of meteorology to society.” The prize website gives examples of, among other things, innovative ways of observing and innovative applications of existing technology. You even mention the development of useful mobile weather apps. I’m tempted to call it “innovation by meteorology” rather than “innovation in meteorology”. Where is the emphasis in your search for winners?

You raise a subtle point, and the answer is “both.” Ideas could include new ways of observing the atmosphere and related environment, new ways of forecasting atmospheric phenomena, or new ways of applying meteorological data, information, and/or forecasts to useful applications. Key words are new and creative. Incremental, relatively minor advances in methods or technologies are not likely to win the Prize. We are looking for “out of the box” ideas, original ideas which may appear surprising.

Can you imagine this prize being won by someone who isn’t even a meteorologist, perhaps a clever business idea or innovative teacher (educational ideas being included)? How do you judge such diverse innovations against each other on societal impact?

We can certainly imagine winning ideas coming from outside the field of meteorology, and in fact we would not be surprised to see innovations coming from people with backgrounds or fields quite different from meteorology. Perhaps the idea will come from someone looking for a solution to his or her problem that depends on meteorology, or a creative person from the arts or a scientific field other than meteorology. Ranking such diverse ideas could be difficult, but ultimately it comes to a judgment call by the Board after thorough discussion of the competing ideas.

The list of potential past prize ideas also includes climate adaptation…specifically, “using uncertainty in climate projections in a cost-effective adaptation technique”. How broadly construed is your definition of meteorology for the purposes of the prize?

We have a broad and open-minded Board and will consider seriously a broad range of ideas. Certainly ideas from fields that neighbor meteorology are encouraged, such as oceanography, air quality, climate, and space weather. I can also imagine a winner coming from education, information technology or communication. There needs to be a strong relationship to meteorology and potential applications to benefit society, however.

You say you’re not looking for “relatively small improvements” in existing ideas…perhaps you can give an example of what might be too small an innovation?

This is clearly a judgment call, but a slightly different way of displaying radar or satellite data on a personal device or a higher-resolution forecast model might be examples of incremental improvements that would not compete well. The important point is that we are encouraging people to really brainstorm and think of brand new ideas. These ideas do not have to be well developed, nor do they need to be proven. I sat down one evening with a glass of wine and let my mind wander, and in only an hour I came up with four very different ideas that I would have considered as competitive had they been submitted by a contestant. Naturally I am not applying for the Prize!

The prize is for ideas that are not just innovative but also practical, and realizable—why all three criteria and how would you define practical v. realizable?

Innovative is obvious—we are looking for new, original, creative ideas. Practical means that the idea could lead to an application in a relatively short amount of time, perhaps a few years, but not decades or longer. Thus a basic research idea that might or might not lead to applications many years down the road would not be appropriate. Realizable means that the idea could be implemented with a reasonable amount of effort and investment and would not run afoul of any physical laws or ethical issues.

How far along toward realization does the idea have to be? What sort of proof of practicality does the committee want when, at the same time, you’re not looking for ideas that are “well developed, implemented, or published”?

This is a very important question. We do NOT require that the idea be very far along in development or implementation. It is conceivable that someone could win with an idea that was not developed at all, but was described in enough detail for us to judge that the idea could be developed and implemented. In fact, we offer to help with the development of the ideas should the winner wish.

I can imagine some people might want to keep their best ideas for this prize under wraps until they’ve had a chance to establish them, perhaps profit from them. How do you convince people to apply with ideas that aren’t yet published or might later reap profitability?

We hope that this is not a serious issue. If someone has a great idea that is in an early stage of development, please send it in! We will protect the intellectual property of the proposer and make public only the broad outlines of the idea. We will also work with the proposer of the idea in any announcements of the winning idea. Finally, the amount of the prize itself is likely to help develop patents or property rights protection.

How often do you overhear ideas at meetings, workshops, etc., that seem to you to fit these qualifications? Are such ideas rare, even in our community?

I do not hear the type of ideas we are seeking very often in such fora. I think really fresh ideas are rare because most people are thinking of incremental advances as part of their jobs—better meteorological displays, higher resolution models and forecasts, more accurate forecasts, better use of ensemble techniques, more accurate or lower cost sensors, higher spectral resolution satellite observations, etc. But if people tried, I think they would be surprised at how creative they could be.

In the first round of the prize last year two honorable mentions were given out, but no first prize. What does this say about the minimum standards the Foundation is trying to establish for such a big prize?

The first prize is 25,000 Euros. That is a substantial prize and the Board wants to set reasonably high standards for winning ideas. But the standard should not be so high as to make it nearly impossible to win.

The foundation says “efforts of large teams in which the original idea cannot be clearly associated with an individual or a small group of individuals (maximum 3) will not be considered.” Why not consider prizes for large groups?

We want to reward individuals or very small groups that come up with a new idea. It is unlikely that a new creative idea will be generated by a large group of people. A large group might be necessary to implement an idea, but the idea itself is likely to originate from one or two people.

Winners will retain full rights to their ideas but when wanted help is offered to realize the winning ideas. What sort of help, under what conditions, does the Prize foundation offer?

We would discuss the possibilities with the winner. We might advise the person on how to implement the idea, and perhaps put the person in contact with an appropriate private company, university, or government lab that could help the person implement the idea.

What is your goal for the prize, in terms of the kind of impact the Prize can have on the community, or change it can bring about?

In the best case an idea would result in a new product or type of information that would generate revenue through a private company while supporting society by producing useful information or predictions, saving lives and property, improving the quality of life, and creating an economic benefit—an idea that would make a significant difference for the better.

Investigating Tornado Fatalities

Men, particularly the elderly, die at a disproportionately higher rate than other population groups. It’s a well-known fact to those studying tornado fatalities, but what researchers are trying to find is a way to keep more of these high risk men responsive to alerts and therefore save lives.

Wednesday morning at the AMS Annual Meeting, several researchers discussed their research on tornado fatalities. The policy session, chaired by Kimberly E. Klockow of the University of Oklahoma, showed that social sciences and data collection methods are improving the way we can analyze deadly storms and adequately warn the public before these storms strike.

Amber Cannon of the University of Oklahoma started the discussion with a comparison of data from tornado outbreaks in Alabama on 3 April 1974 and 27 April 2011. She noted that, although more people died in the 2011 outbreaks than in 1974, the population density had increased during that time. As a result, the fatality rates very similar.

If the death rate isn’t going up, then maybe we can bring it down. Shadya Sanders, from Howard University, presented her research regarding the super outbreak of tornadoes in 2011. She found that, while a 45% tornado risk seems huge to a meteorologist, the average person may not see the gravity of such a situation. Her work with focus groups has shown the importance of education for children and risk awareness for adults.

Soon, according to Hope-Anne Weldon of the University of Oklahoma, there will be a “one-stop shop” for killer tornado information from the NOAA/NWS Storm Prediction Center. Weldon spent an entire summer filling in gaps in data about tornado victims, clarifying tags of age, gender, and domicile in statistics for 1991-2010–in all 400 tornadoes killing more than 1,100 people. With more detailed data, she noted, social scientists will be able to draw even better conclusions.