This year’s AMS Annual Meeting provided no shortage of memorable presentations. The focus on 2017’s hurricanes in particular yielded some of the most memorable moments, and now you can listen (again, or for the first time) for yourself. Recorded presentations are being uploaded gradually to the AMS meeting program site.

Richard Alley’s speech at the Presidential Forum was the first to go online, here including AMS President Roger Wakimoto’s introduction as well as questions from the audience:

Here’s a portion of Dr. Alley’s memorable riff on our semi-aware relationship to the science and technology we carry around in our pockets every day:

I’m a Newtonian physicist. I didn’t take quantum, I didn’t take relativity. But my understand is that the nice lady in the (cell) phone using the GPS is using both general and special relativity. Because down here, she is deeper in Earth’s gravity well and she is moving slower than the clocks on the satellite. And the correction from relativity is about 10 km a day. And she can do 10 km pretty easily. Which means if she didn’t have relativity, she would get lost in about two minutes. And that’s … We get where we’re going not only because of quantum mechanics but also because of Einstein. And, no, she will not fall for you because she’s canoodling with Einstein in the phone here.

But you know how these things work. Right? … I’ve been working on ice since 1977, the summer after my freshman year. My teachers, in geology and other things, I think if you were to ask them what is the most useless and esoteric science you can think of, they might have said relativity and quantum mechanics. And you’ve got relativity and quantum mechanics in your phone, in your pocket, and you can’t really think of living the life you now live if we didn’t understand relativity and quantum mechanics….

Climate science is not this new-fangled stuff you’ve got in your cell phone … it’s been with us for a long time. But I can tell you, and some of you out there know this as well, that there are people—good people, neighbors, people who pay our salaries—who will pull out their cell phone and send me a note saying, ‘You’re an evil liar. You should be fired.’ They go to my president and try to get me fired. Because I’m talking about this global nonsense. ‘These scientists are just trying to take away our pickup trucks.’ And they do it with a cell phone. And they are, I think, all across the board, good people. Some of them have been misled. And that’s something we have to come back to.

Also online now are the talks from the web-streamed Presidential Town Hall on the hurricane season. Well worth a listen while you’re waiting for more talks to appear online, like this reaction to forecasting Hurricane Irma, from NBC-6 Miami Chief Meteorologist John Toohey-Morales:

In South Florida I’m known as the non-alarmist guy. I mean if you want a just-the-facts-and-he’s-not-at-all-that-excited-about-this-tropical-cyclone guy, I’m your person … But with Hurricane Irma … on Friday night … National Weather Service Key West … about to go into full-Katrina mode: catastrophic, life threatening, and those types of messages were about to go out … what does the non-alarmist guy do? (Plays video of his TV broadcast that Friday night.) ‘If you’re sitting on a Florida Key right now—What the heck are ya doing? Get out! Now!’

Or this zinger from FEMA’s Tony Robinson, while talking about Hurricane Harvey:

Working with our counterparts in the state of Louisiana a guy said, ‘I finally figured out your flood codes on when I should have flood insurance.’ And I said, ‘Oh, yeah? What’s that?’ He said, ‘Your driver’s license says Louisiana, you aughta have flood insurance.’ That’s a public service announcement right there. There’s 144 days to the start of the 2018 hurricane season.”

But it was Ada Monzon, WIPR TV/WKAQ Radio, San Juan, who drew a rare standing ovation after her heartfelt presentation on Hurricane Maria:

And I can tell you, that in my 30 years as a meteorologist in Puerto Rico, even going through Hugo and Georges and more than 10 other tropical storms … (I’m sorry) … For the first time in my life I was afraid. Not because of the wind or the storm surge or the rain. I was afraid [for] the future of Puerto Rico. … Still to this day there are great discrepancies on how many people died in Puerto Rico because of Maria. By government information, there were 64 dead. Our other entities have informed … of more than 1,000 dead. … The response and recovery efforts have been very slow and complicated. More than three months after the hurricane, near 45% of the island is still without power. Many are suffering. More than 100,000 people have left the island in the last three months, to Florida, New York, Texas. … Enduring two major hurricanes has been hard. But at the same time it has served a vast lesson to all our society: We need to find a way of living with natural disasters and other potential catastrophic events and we need to work harder as meteorologists and scientists to educate our public through all means of communication, especially social media.

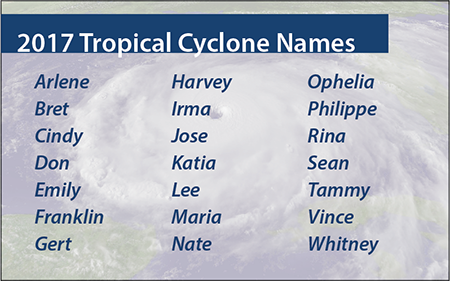

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has begun. If they haven’t already, people who could be affected by tropical storms and hurricanes should prepare now for the six-month season, which ends November 30 and encompasses the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico.

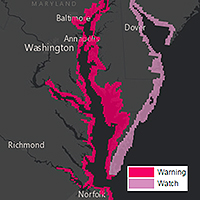

The 2017 Atlantic hurricane season has begun. If they haven’t already, people who could be affected by tropical storms and hurricanes should prepare now for the six-month season, which ends November 30 and encompasses the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea, and Gulf of Mexico. Storm surge watches will be issued within 48 hours of possible life-threatening coastal inundation. Storm surge warnings will be issued at least 36 hours before the danger of life-threatening coastal inundation is realized. The new graphical products will be issued in tandem with NHC’s Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map, which quantifies the expected inundation from storm surge and indicates the depth of the flooding on land.

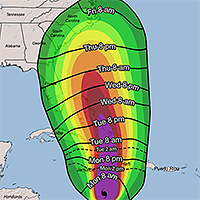

Storm surge watches will be issued within 48 hours of possible life-threatening coastal inundation. Storm surge warnings will be issued at least 36 hours before the danger of life-threatening coastal inundation is realized. The new graphical products will be issued in tandem with NHC’s Potential Storm Surge Flooding Map, which quantifies the expected inundation from storm surge and indicates the depth of the flooding on land. Additionally, NHC will introduce a map to provide guidance on when users should have their preparations completed before a storm. These experimental graphics will show Time of Arrival of Tropical-Storm-Force Winds—a critical planning threshold for coastal communities. Many preparations become difficult or dangerous once tropical storm conditions begin.

Additionally, NHC will introduce a map to provide guidance on when users should have their preparations completed before a storm. These experimental graphics will show Time of Arrival of Tropical-Storm-Force Winds—a critical planning threshold for coastal communities. Many preparations become difficult or dangerous once tropical storm conditions begin.