Rick Knabb has been named the new director of NOAA’s National Hurricane Center. He replaces outgoing director Bill Read and begins June 4, days after the official start of the six-month Atlantic hurricane season on June 1.

Well-known as The Weather Channel’s “hurricane expert” for the last two hurricane seasons, Knabb is returning to familiar territory. He was a senior hurricane specialist from 2005 to 2008, and the Center’s science operations officer beginning in 2001.

“I’m ready to reunite with the talented staff at the National Hurricane Center and to work with all of our partners to prepare everyone for the next hurricane,” said Knabb. “Personal preparedness will be critically important, including for my own family and home.”

Born just outside of Chicago, Knabb grew up in Coral Springs, Florida, near Fort Lauderdale, and in Katy, Texas in suburban Houston. He earned a bachelor’s degree in Atmospheric Science from Purdue University and holds a master’s degree and Ph.D. in Meteorology from Florida State University.

Knabb left the Hurricane Center in Miami and became deputy director of the Central Pacific Hurricane Center (CPHC) in Honolulu, Hawaii, for a year before arriving at The Weather Channel. The CPHC oversees tropical cyclone forecasts and warnings from 140° west longitude westward to the International Dateline, including all of the Hawaiian Islands.

A member of the AMS, Knabb also serves on the AMS Board for Operational Government Meteorologists. He has published numerous papers in AMS and other scientific journals and has given presentations on hurricanes and tropical weather at AMS and related conferences. His expertise in communicating has been honed these last two years at The Weather Channel.

“Rick personifies that calm, clear, and trusted voice that the nation has come to rely on,” says NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco. “Rick will also lead our hurricane center team and work closely with federal, state and local emergency management authorities to ensure the public is prepared to weather the storm.”

Chris

Chris

Eurasian Cold Snap a Product of Arctic Warmth

In a paradox that it seems only nature can muster—like quelling a year-long drought in the western two-thirds of Texas with record snows—it turns out that warming going on in the Arctic this winter is the likely culprit behind killer cold and snow that had been plaguing Eastern Europe since late January. And it is now also likely linked to the colder-than-normal winter occurring in Japan and Western Asia.

Weather patterns since the fall have set up in such a way as to leave large expanses of Arctic Ocean, particularly the Barents and Kara Seas north of Scandinavia and Russia, nearly ice-free. In fact, an image from early February posted to the Arctic Sea Ice Blog shows this area north of the Arctic Circle as open water for the first time in what it refers to as the “new Arctic regime (2005-present),” when it should be completely frozen over.

The changing weather patterns resulting from this new era of record sea ice melt seem to have helped build up a huge helping of frigid air over Siberia that came crashing southward as soon as the storm track shifted, which it inevitably does throughout the year. Instead of Western Europe like the last two winters, this time the bitter cold targeted Eastern Europe, delivering snow-laden storms to nations of the Eastern Mediterranean and even North Africa, as well as far Western Asia, Korea, and Japan.

Numerous researchers have been working the last few years to figure out what’s going on. The environmental news and technology site Bits of Science wrote a timely online article explaining the findings of recent published research and then tying the studies to the different teleconnections patterns that influence Eurasia’s winter weather — the Arctic Oscillation and its focused cousin, the North Atlantic Oscillation. Together, these pressure anomaly-driven climate patterns can dictate where winter’s worst cold and snow and best warmth become established.

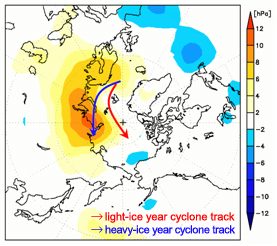

A new study headed for publication in the Journal of Climate in March further extends the influence of the warming Arctic. The article by the Research Institute for Global Change’s Jun Inoue et al. contends that the storm track over the Barents and Lara Seas takes a more northerly route when sea ice there is reduced. In a positive feedback mechanism, the northward-shifted storm track pulls warm air over the Arctic Ocean. At the same time, cold air builds over Siberia and the Norwegian coast, and becomes poised to spill southward, or to the west and the east.

“Such warm Arctic and cold continental conditions are referred to as a warm-Arctic cold-Siberian (WACS) anomaly, and the WACS anomaly could be a procurer of severe weather in the downstream region,” the authors report.

As with the collective research on the warming Arctic’s influence on mid-latitude winter weather, Inoue et al. conclude that using sea-ice variability from this region of the Arctic would improve the reliability of the seasonal weather predictions in individual years.

Avid Surfer, Forecaster Receives Joanne Simpson Award for Sustained Mentorship of Colleagues

Mark Willis, a development manager and forecast strategist for Surfline—the go-to global surfing forecast company—is the 2012, and first, recipient of The Joanne Simpson Mentorship Award. Willis, a lifelong surfer who is at home when the surf is cranking, won the award for aiding NWS volunteer interns in gaining experience valuable to their future careers through dedicated mentorship, and sustained encouragement and guidance.

The Front Page set out to learn more about Willis and his penchant for mentoring. He worked for Surfline for several years in the late 1990s and early 2000s before joining the NWS Eastern Region marine program. Then, recently, he returned to Surfline. The following is our Q and A session in which Willis sheds some light on his particular style of engagement with colleagues.

What’s your area of expertise in meteorology? And did that help you secure the most recent position you had with NOAA?

My expertise is in marine and coastal forecasting, but I enjoy all aspects of meteorology and oceanography. My marine background definitely helped me secure my last position at NOAA as the Marine Program Manager at NWS Eastern Region Headquarters.

What was your passion that got you into marine forecasting?

I became interested in marine forecasting through surfing. I grew up surfing on the East Coast and became fascinated by waves and how they changed so quickly. I learned much of the science behind wave forecasting on my own and by working at Surfline as its difficult to get much formal training on the subject. I became involved in ocean wave modeling in graduate school and continued to work on wave modeling projects in the NWS. I’ve been lucky to be able to work in forecast offices that have marine responsibility as this has greatly enhanced my knowledge of the ocean and the atmosphere.

What is your current title and affiliation, and what is it you now do?

Global Forecast Development Manager/Lead Forecast Strategist with Surfline, Inc. Surfline also owns Buoyweather.com and Beachlive.com. My job is to lead Surfline/Buoyweather/Beachlive’s push into international markets and also help to fine tune existing products and develop future products.

Who were the folks you were mentoring?

I have mentored several students and employees throughout my career as a meteorologist. I mentored volunteer interns when I was a forecaster at the NWS forecast office in Newport/Morehead City, North Carolina. Most were college students but I also worked with a couple of high school students. I also mentored new employees when I was the East Coast forecast manager at Surfline in the early 2000s. I have been fortunate that both of my employers have allowed me to mentor, as it’s something I greatly enjoy.

Tell us your philosophy on mentoring and what sets it apart from others’ techniques/methods?

One thing I always thought of when I was working with students and/or new hires was that I was in their shoes not too long ago. I always ask myself, “What would have made me grow and feel more comfortable?” The answer to that was always the same – just make sure they feel welcome, included during forecast decisions, and find the right times to train and teach. I think it’s important not to continuously throw things like QG theory down their throats and show them how much you know. It’s more important to get to know the person, find their learning style, and adapt to the human being. Most of all, get to know who they really are, ask about their family, hobbies, find their true interests in meteorology and just try to educate and mentor where you can.

As far as what sets that apart from others’ techniques/methods – I’m honestly not sure. I did take the student that nominated me for this out surfing a couple of times though where we talked about life and exchanged waves, so maybe that’s what set it apart!

How do you use that to promote excellence in forecasting/the atmospheric sciences?

I just try to be a hard worker, lead by example, and follow my passions. Hopefully that promotes excellence in our ever so humbling field.

Will you continue to mentor in your new position?

Every chance I get. I also hope I get the opportunity to be mentored by some of the veterans at Surfline as well, as they have an incredible staff with the best group of marine/surf forecasters and modelers in the world. Surfline is always looking for the brightest and the best so hopefully I’ll get the opportunity to mentor new employees in the future.

When you first learned you were going to receive this particular award, what was your reaction?

I was shocked when Jon [Malay] called me to tell me the news, honestly. This award is hands down one of the highlights of my career. I have a great sense of pride in the fact that the students and colleagues I mentored went out of their way to nominate me for this.

One additional thing I’d like to highlight on this subject is that the news of the award came right after a very stressful period of dealing with Hurricane Irene both professionally and personally. The award definitely lifted my spirits after that!

What advice would you give a colleague who wanted to win this same award next year?

Be yourself, get to know the people you are mentoring, and find good entry points to train and mentor. Don’t force it.

What single piece of wisdom would you hope those you mentored would carry into their careers?

As the late Sean Collins (founder of Surfline) taught me and inscribed into the Surfers’ Hall of Fame—“Follow your Passions.” You’ll perform much better and find more satisfaction in your career if you enjoy what you are doing.

Hazardous Weather Testbed Team Wins 2012 Spengler Award for Severe Storm Collaboration

The 2012 Kenneth C. Spengler Award recipient is a team of eight scientists and forecasters with the NOAA Hazardous Weather Testbed (HWT). Their collaborative efforts are being acknowledged for bringing the government, academic, and private sectors together in a visionary, proactive, and exemplary manner to deal with the challenges posed by hazardous weather.

The HWT, a facility jointly managed by NSSL, the Storm Prediction Center (SPC), and the NWS Oklahoma City/Norman Weather Forecast Office (OUN), is leading the way to engage the weather enterprise in turning severe storm research into operations.

HWT team members are John “Jack” Kain, Steve Weiss, Russell Schneider, Mike Coniglio, Greg Carbon, David Bright, Jason Levit, and Jay Liang. The Front Page met with Schneider (SPC director) and Weiss (SPC chief of support) to learn more about HWT, its dual programs focused on warnings and forecasts, and the advances HWT has championed as well as the challenges that remain.

The full interview is available below.

2012 Remote Sensing Prize Winner Sees Polarimetric Radar Research Go Nationwide

Viswanathan N. “V.N.” Bringi, professor emeritus of electrical and computer engineering at Colorado State University, is the 2012 recipient of the AMS Remote Sensing Prize. Known to many simply as “Bringi,” his career-long research and development of dual-polarization technology earned him this honor for his outstanding contributions to the advancement of polarimetric Doppler weather radar.

The Front Page sat down with Bringi at the 92nd AMS Annual Meeting in New Orleans last week to learn more about his research as well as the development of polarimetric radar into an advanced forecast tool. You can listen to the interview below.

Bringi spent decades working with what he describes as a relatively simple idea to perfect the complex technology and to convince experimental radar meteorologists that it could be used in operational forecasting. His efforts paid off and his legacy was written when the NWS announced in 2011 that it would be upgrading its nationwide network of 159 Doppler weather radars with dual-polarization technology. NSSL states that the potential benefits with dual polarization will be “as significant as the nationwide upgrade to Doppler radar in the 1980s.”

While Bringi anticipated it would eventually occur, he added, “I was greatly elated that the upgrade would happen before I retired.” The upgrade of the Doppler radar network is expected to be completed this year, concurrent with Bringi’s change in status at CSU to professor, emeritus.

The 2012 Jule G. Charney Award Winner Strives to Simulate Complex Clouds, Rid Models of Errors

Chris Bretherton, professor in the University of Washington Departments of Atmospheric Science and Applied Mathematics, is the recipient of the 2012 Jule G. Charney Award. He received this distinction for fundamental contributions to our understanding of atmospheric moist convection, particularly the discovery of mechanisms governing the transition from stratocumulus to shallow cumulus convection.

In a video interview, which you can view below, Bretherton discusses his research accomplishments and what he is looking forward to working on next: ridding models of cloud feedbacks on climate. In addition, he also mentions that he isn’t the first member of his family to win The Jule G. Charney Award, which is in the form of a medallion. In an email sent to The Front Page, he explains the connection, and also tells how he got his start in atmospheric research:

“I have a distinguished family history in meteorology. My father, Francis Bretherton, was awarded the first Jule Charney award in 1983 for his work in areas of geophysical fluid dynamics ranging from internal gravity wave dynamics to frontogenesis to ocean eddy processes. I have a very similar skill set, and I have always loved mountaineering and other outdoor sports, where weather is of paramount importance. Thus, I was also drawn into the field.”

2012 Verner E. Suomi Award Recognizes Extensive Field Work to Understand Ozone Dynamics

Anne Thompson, professor of meteorology at Penn State, is the 2012 recipient of The Verner E. Suomi Award. She is being recognized with the Suomi Award, which is in the form of a medallion, for exceptional vision and leadership in deploying technologies that have significantly advanced the understanding of ozone dynamics in the atmosphere.

The Front Page sat down with Dr. Thompson to learn more about her research accomplishments and her passion for field programs, which produced huge amounts of data, allowing her to unlock the secrets of ozone dynamics. She also extends that passion to students who sometimes need prompting to participate in field work , willing them to “open your eyes and get involved.”

Click on the image below to view the interview.

Broadcast Meteorology Award Winner Says 'Be Yourself' On-Air

Bob Ryan, meteorologist for WJLA-TV in Washington, D.C., is the 2012 recipient of The AMS Award for Broadcast Meteorology. Ryan is being honored with this annual award in recognition of a career based on personal integrity and dedication to advancing the science of meteorology through broadcasting, education, promotion of safety, and support of colleagues.

Established in 1975, the AMS Award for Broadcast Meteorology recognizes a broadcast meteorologist for sustained long-term contributions to the community through the broadcast media, or for outstanding work during a specific weather event. Ryan, who has been a fixture in Washington TV News for more than three decades, will receive the award at the 92nd AMS Awards Banquet Wednesday evening in New Orleans.

The Front Page caught up with him to learn about how he connects with viewers when on-air and with his colleagues within the AMS. His primary advice for future broadcast meteorologists: “Be yourself,” he says, “and again, you’re talking to one person.” You can view interview below.

NASA Mission Monitors Birth of Antarctic Iceberg

Resuming a multi-year mission to map Antarctic ice in mid October, NASA researchers discovered a miles-long crack in a major glacier that marks the beginning of a new mammoth iceberg. Operation IceBridge scientists flying in a specially instrumented DC-8 jet returned soon after to make the first-ever detailed airborne measurements of giant iceberg calving in progress.

The crack in Pine Island Glacier, which extends at least 18 miles (29 km) and is 165 feet (50 meters) deep—enough to swallow up the Statue of Liberty— could break free a chunk of ice more than 340 square miles (880 square km) in size from the vulnerable West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

Pine Island Glacier’s ice shelf mostly floats, extending its unstable arm as many as 30 miles (48 km) away from the Antarctic landmass that grounds it some 500 meters (1,640 feet) below the surface. As the glacial ice inland flows slowly toward the sea and feeds the shelf, the arm eventually breaks, calving huge icebergs.

Pine Island Glacier last calved a significant iceberg in 2001, and some scientists have speculated recently that it was primed to calve again. But until an Oct. 14 IceBridge flight of NASA’s DC-8, no one had seen any evidence of the ice shelf beginning to break apart. Since then, a closer look back at satellite imagery seems to reveal the first signs of the crack beginning to cut across the ice shelf in early October.

“It’s part of a natural process, but it’s pretty exciting to be here and actually observe it while it happens,” says Operation IceBridge project scientist Michael Studinger of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center.

The IceBridge team thinks that once the iceberg breaks free, it will leave behind the shortest extending arm of the Pine Island Glacier since recordkeeping began in the 1940s.

Pine Island Glacier is of particular interest to scientists because it is big and unstable, which makes it one of the largest sources of uncertainty in global sea level-rise projections. A collapse of the entire West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) is one of the nightmare scenarios climate forecasters envision in a warming world. If the WAIS were to melt, it could raise sea levels worldwide 20 feet.

NASA’s Operation IceBridge, the largest airborne survey of Earth’s polar ice ever flown, is in the midst of its third field campaign from Punta Arenas, Chile. The six-year mission will yield an unprecedented three-dimensional view of Antarctic ice sheets, ice shelves, and sea ice.

NOAA: 'Unmistakable' Global Warming Continues

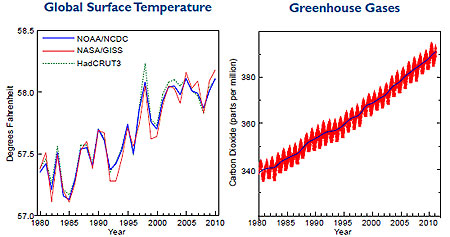

NOAA released the 2010 edition of its annual State of the Climate report this week revealing that Earth’s atmospheric and oceanic temperatures are rising unabated. The 218-page report, consisting of the peer-reviewed conclusions of more than 350 researchers in 45 nations, will be distributed with the June issue of the Bulletin of the AMS.

A press briefing summarizing the report’s findings noted a “consistent and unmistakable signal from the top of the atmosphere to the bottom of the oceans” that the world continues to warm.

Those signals include last year’s global surface temperatures virtually tying 2005 as the warmest in the reliable global record, which dates to 1980. The Arctic warmed about twice as fast as the rest of the world, reducing sea ice extent to its third lowest level on record.

The area of Arctic sea ice was so small in September that for the first time in modern history both the Northwest Passage through northern Canada’s usually ice-bound islands as well as the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s northern coast were open for navigation.

Average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) worldwide were third warmest on record in 2010. This was despite a nearly 2°F SST drop since 2009 as major El Niño warming of the tropical Eastern Pacific during the first half of 2010 rapidly transitioned to a major La Niña cooling event.

Greenland’s ice sheet lost more mass in 2010 than in any year during the last decade. The melt rate was nearly 10 percent more than the previous record year for loss, 2007. Mountain glaciers globally lost mass for the 20th straight year.

Additionally, global ocean heat content last year was among the warmest on record, following the trend of 2009. Warmer oceans combined with glacial melting to increase average sea levels around the world.

Climate indicators tracked in the State of the Climate during 2010 also included precipitation, greenhouse gases, humidity, cloud cover and type, temperature and saltiness of the ocean, and snow cover.

The report indicated that the concentration of carbon dioxide continued to rise in 2010, surpassing 390 parts per million (ppm) for the first time. In 1979, the CO2 concentration reached 340 ppm.

The 2010 Climate Report also notes that the oceans were found to be saltier than usual in some areas, due to increased evaporation of the sea surface, and less salty, or “fresher,” than average where precipitation was more than is typical. Researchers conclude in the report that this is a sign that Earth’s water cycle is intensifying, which will lead to heavier rainfall and snow events worldwide.

Such events reached extremes in 2010, assisted in part by the transition to La Niña as well as an extraordinarily abnormal pressure anomaly in the northern Atlantic Ocean referred to as the North Atlantic Oscillation (NAO). Helping to create a blocking weather pattern over Greenland, and generating huge undulations in the jet stream, the NAO in early 2010 resulted in a lopsided winter in North America with warmer- and drier-than-usual weather in much of Canada and frigid and snowy weather in the Eastern third of the United States), and the coldest winter in more than 30 years in the United Kingdom.

While this blocking pattern eased its extreme grip across North America and Western Europe into summer, continued amplification of ridges and troughs downstream across Asia contributed to a searing summer heatwave in Russia and epic flooding in Pakistan. More than two months of above-average temperatures, including all-time record heat in Moscow, resulted in at least 14,000 heat-related deaths as well as choking wildfires. At the same time, extreme monsoon rains inundated a fifth of Pakistan, displacing more than 20 million people in normally fertile flood plains.

The year 2010 ended with unprecedented flooding across eastern Australia. The lingering La Niña pattern coupled with the enhancement in the water cycle led to the region’s wettest spring (September–November) since record keeping began 111 years ago. December precipitation in the state of Queensland was more than double the average amount, which led to massive flooding where entire geographical regions of the nation—not just cities and towns—were under water.

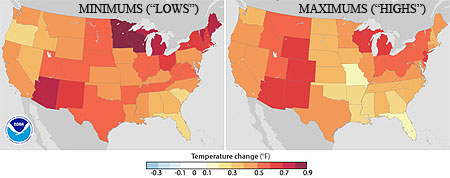

The overall consensus, especially when considering the dire predictions of an increasingly warmer world, is that the events and records of 2010 are the new normal on planet Earth. In one way, NOAA is confirming this today, releasing its new “climate normals” for temperature and precipitation for the United States, which serve to put into perspective current extremes based on the changing climate of the most-recent 30 years of data. The new climate “normals” valid for the period 1981-2010 have increased in temperature just as the State of the Climate has observed. Comparing the new temperature normals to those of the past decade—the period 1971-2000—shows they’ve increased by 0.5°F in that 10-year period over the United States.

“The [global] climate of the 2000s is about 1.5°F warmer than the 1970s, so we would expect the updated 30-year normals to be warmer,” NOAA National Climatic Data Center Director Thomas R. Karl says with regard to the new report.