by Jen Henderson, Skywarn storm spotter, writer, and grad student at Virginia Tech in Science and Technology Studies. Republished from her blog at JenHenderson.com

This week, I’d like to have a little chat with my friends and colleagues who are connected to the world of atmospheric and meteorological sciences: Faculty members, industry professionals, employees of NOAA and the National Weather Service (NWS). And yes, this includes my fellow graduate students in these fields, as well.

Here’s a little story:

Last week, as I sat in front of a computer at a local NWS office,  I found myself mesmerized by the most simple of objects: a weather balloon.

I found myself mesmerized by the most simple of objects: a weather balloon.

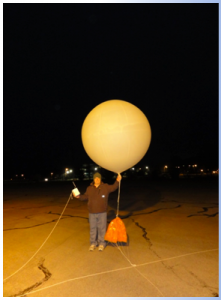

In the photograph in front of me, a meteorologist stood dressed in a warm jacket, jeans, and hat gripping a thin cotton string topped by a whitish orb. It hovered like a small sun over his left shoulder. I recalled the time I watched a weather balloon launch a few months ago, how carefully the meteorologist measured the helium that inflated the balloon, which before it filled with air sat on the table like a large loaf of bread dough. I helped him inspect it for defects before following him out into the dusk of an early autumn evening where he released it into the cloudy sky above. He would later tell me that launching the balloon, and the small brick-like rawinsonde that dangled below on its journey into the upper atmosphere, was still one of the most reliable means for collecting data important to weather forecasting.

My question that day was how to get members of different publics as excited about weather as I then felt. What kind of research were meteorologists able to do based on this weather balloon launch, or sounding? What did the launch reveal about trends in weather? Where might people like me, a graduate student in a discipline outside the sciences, learn more?

- What I really want to know was this: How might meteorologists and atmospheric scientists more successfully communicate what they do to those of us who are not familiar with their work? How might they channel the passion they have for what they do into stories that inspire the rest of us?

Communicating sciences to various publics has been on my mind for several years, but it was brought home to me last summer when I attended the American Meteorological Society’s annual Policy Colloquium in Washington, D.C. I was one of a few social scientists to mingle with and learn from various atmospheric and meteorological scientists, ranging in experience from graduate school students to tenured professors and industry professionals. While the colloquium centered on introducing attendees to several aspects of the policy world, which is rich in opportunities and complexity, the underlying theme, you might say, focused on encouraging scientists to think about their potential role in communicating what they do to different publics–policy makers, elected officials, students, and members of the general public.

As I listened to seasoned speakers from all walks of life, I gained a few unexpected insights into science policy and scientists themselves.

- Many scientists harbor the assumption that they’re not good at communicating their work. Not true! I heard many of my scientist colleagues refer to themselves as bad communicators, introverts, and pointy-headed thinkers. They insisted they didn’t know how to communicate (although they did have an inkling about how important it is that they do so). What I experienced instead was the opposite. Most of the participants were excellent story tellers and more than adequate communicators, they just hadn’t thought about the intersection of their narrative and research skills. With a little practice (and a lot of critique), many left the colloquium more confident about their ability to explain not only their work but why it might be important to different audiences.

- Science affects policy and policy affects science. In fact, I would suggest that the two are intertwined in ways that make it difficult to distinguish them at times. Issues surrounding funding, regulation, and accountability shape the types of science we do and the ways in which it gets done. And then of course the types of science performed across the country affect and influence policy. See how they’re intertwined? There is no pure science nor is there pure policy. As they say in my discipline, Science and Technology Studies, they are co-constructed.

AMS policy group at Mount Vernon. - There are multiple ways to participate in communicating sciences to your chosen public. With the help of communications staff members from The American Geophysical Union (AGU), we practiced distilling lengthy research agendas into a few sentences that could resonate with a listener. AGU staff encouraged us to think about the story of our research, the narrative hook that would capture someone’s interest; to practice talking about our research with school children, members of the media, even through socia media sites; and to consider building a relationship with our local government officials, many of whom have little scientific background but must make decisions involving scientific information. (For a concise way of thinking about how scientists can act in multiple ways, read The Honest Broker, by Roger Pielke, Jr., or check out his awesome blog.)*

So what’s my overall message?

You, my friends, have the opportunity to join an amazing group of people at the American Meteorological Society who believe that the passion each of you feel about your work can be productively channeled into the science policy world…and beyond. The same elements of the universe that inspire you to pursue your research can inspire others. Your experience can give you a voice in shaping the multiple conversations among members of the public, policy makers, industry professionals, local government officials, and your fellow colleagues.

I wish I could attend again. The colloquium opened up opportunities and allowed me to make connections I wouldn’t have had otherwise. It helped me understand the challenges of the political world and how these issues shape my own work. And it was so much fun!

The AMS Policy Colloquium is now accepting applications for the next cohort who will meet in DC for nine days this June. But hurry, the deadline is March 31. If you’re a student or faculty member and you’re accepted, you can apply for NSF funding. So what have you got to lose?

*To read more about science policy, the AMS colloquium, and how these two things have shaped my work and my colleagues’ work, please check out our article in the February 19, 2013 issue of Eos, the AGU’s weekly newspaper. Goldner, Henderson, and Shieh.