by Christopher C. Burt

Editor’s note: The article by El Fadi et al. published on-line today by the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society is literally a record-setting contribution to climatology. Co-author Chris Burt tells the story behind the story.

As any weather aficionado can avow, Earth’s most iconic weather record has long been the legendary all-time hottest temperature of 58°C (136.4°F) measured at El Azizia (many variant spellings), Libya on September 13, 1922. It is a figure that has been for meteorologists as Mt. Everest is for geographers. For the past 90 years, no place on Earth has come close to beating this reading from El Azizia, and for good reason–the record is simply not believable.

In early March 2010 I was included in an e-mail loop concerning questions about this record. The e-mail discussion participants at that time included Maximiliano Herrera, an Italian temperature researcher based in Bangkok; Piotr Djakow a Polish weather researcher; and Khalid Ibrahim El Fadli, director of the climate department at the Libyan National Meteorological Center (LNMC) in Tripoli.

Previous to this discussion I had generally considered the Libyan world record as acceptable although suspicious. The figure had been around for 90 years and two previous studies by Amilcare Fantoli (who was the man responsible for verifying the record in 1922) had more or less substantiated the extreme 58°C figure.

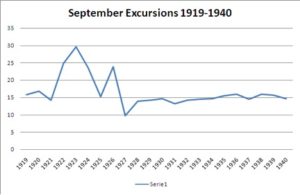

However, Piotr produced a chart of the monthly temperature amplitudes at Azizia for each September from 1921-1940 and this chart raised an alarm so far as the validity of the Aziza record was concerned. This was the first time that I began to really think something was not right about the record.

In September 2010 Internet weather provider Weather Underground, Inc., hired me as their ‘Weather Historian’ proposing that I write a weekly blog on extreme weather events and records.

I decided that one of my first blogs should be about the Azizia record. I was intrigued that El Fadli was skeptical of the Azizia 58°C figure and requested more data. El Fadli’s enthusiastic and gracious response (to provide all and any weather data I might be interested in) was beyond my expectations. Past experience had shown me that many national weather bureaus consider their data proprietary and/or subject to excessive fees for access.

With El Fadli’s data on hand and after researching all other references known (to me at the time) concerning the Azizia event, I posted a blog on wunderground.com reflecting my findings on October 3, 2010. I forwarded a copy of this to Dr. Randy Cerveny, a professor at Arizona State University (ASU) and co-Rapporteur of climate and weather extremes for the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

At this point, Randy picked up the ball and created an ad-hoc evaluation committee for the World Meteorological Organization to evaluate the record for the WMO Archive of Weather and Climate Extremes (http://wmo.asu.edu/). After this positive response from Randy I asked El Fadli if Libya officially accepted the Azizia figure. He responded that they did not. Since records like this are, to a degree, the provenance of national interest and El Fadli responded that Libya did not officially accept the colonial-era data from Azizia (measured by Italian authorities at that time in Tripolitania) this became the catalyst to launch an official WMO investigation.

This would be an unprecedented investigation for this WMO extreme records evaluation committee. Rehashing old records is not the WMO Archive’s primary objective, which is to verify new potential records. As Dr. Tom Peterson of the US National Climate Data Center, President of the WMO’s Commission on Climatology of which the Archive is a part, put it, “To be honest, I was reluctant to reopen this question because other people had looked at the record in the past and it had been so widely accepted. I was particularly afraid that it would be an uncertain subjective opinion as to whether it was a bit off or not.”

Nevertheless, the investigation was approved and on February 8, 2011, Randy assembled a blue-ribbon international team of climate experts (eventually 13 atmospheric scientists in all). The official investigation began.

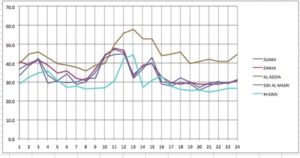

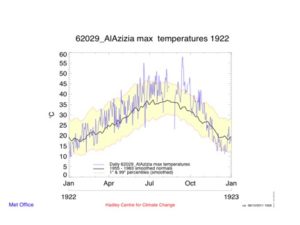

Amazingly, El Fadli had just uncovered a key document: the actual log sheet of the observations made at Azizia in September1922 (see illustration further below). The log sheet clearly illustrated that a change of observers had occurred (as was evidenced by the hand written script) on September 11, 1922, just two days prior to the ostensible record temperature of 58° on September 13th. Furthermore, the new observer had interchanged the Tmin columns with the Tmax columns. Also, beginning on September 11th the Azizia maximum daily temperature records began to exceed those at the four other stations reporting from northwest Libya (Tripolitania) by, on average, 7°C . That trend continued for the rest of the month (with a couple of days of missing data) and into October 1922.

Just as this key discovery (the finding of the original log sheet) was made, the Libyan revolution broke out. On February 15, 2011 we received the last message from El Fadli prior to the revolution. Col. Gaddafi, the leader of Libya, had shut down Libyan international communications.

Of course, without El Fadli’s

critical input we could move no further with the investigation and Randy called for a hiatus to further deliberations.

In early March Gaddafi began airing long nightly rambling tirades on his government TV network. During one of these he made an ominous reference to how NATO forces were using Libyan climate data to plan their assault on the country. My heart sank when I heard this. I immediately thought that our colleague, El Fadli, as director of the LNMC, must have been implicated by Gaddafi as providing weather information to the ‘enemy’.

I must say, at that point, I—and the rest of the committee—thought El Fadli was a dead man.

We didn’t hear again from El Fadli until August 2011 when the revolutionary forces closed in on Tripoli. One of our committee members, WMO chair of the Open Programme Area Group on Monitoring and Analysis of Climate Variability and Change, Dr. Manola Brunet, who knew El Fadli personally had up until then been unable to contact him by phone or email. Then on August 13, 2011 we received our first email from El Fadli.

El Fadli here relates the situation he faced during those long months when we lost communication with him:

During that critical time all communication systems in Libya were shut down by the regime so it was impossible to communicate with anyone, even inside the country. Mobile telephone communications were restricted and even local calls were controlled and monitored. What was amazing however, believe it or not, was that my office satellite internet connection was still up and running. But using such posed serious dangers, if anyone discovered me I would probably lose my life. Hence, I never used that connection. The first 3 months (February-May) I was able to reach my office (my home being about 5 km east of El Azizia and 40 km to my office in Tripoli) but then in May we suffered from short fuel supplies, electricity, and even cooking gas. You can imagine how difficult our lives became! The other serious story involved the security situation. When I borrowed a car belonging to the local United Nations office (since I had no fuel for my own car) I was driving to morning prayers (04:00 am) with my sons and suddenly we came under gunfire from the back and rear of the vehicle. The vehicle was struck as I drove at a crazy speed with our heads ducked low. Our life was spared by the grace of God. This happened in late July.

Then, as we all watched through the technology of television and internet, by September 2011, the dictator Gaddafi was gone … and El Fadli was back!

With the investigation back on track, committee members made further progress in October and November. Dr. David Parker of the U.K. Met Office did a reanalysis of surface conditions across the Libyan region for September 1922. The results displayed a significant departure (up to 6 sigmas) from what the temperature observed at Azizia was to what the reanalysis plotted for the area. This was a key discovery, using technology that had never been available in past investigations of the Libyan record.

Also, Philip Eden of the Royal Meteorological Society and others uncovered information concerning the unreliability of the Bellani-Six type of thermometer that had apparently been used at Azizia in September 1922. Of particular interest was how the slide within the thermometer casing was of a length equivalent to 7°C. It would be easy for an inexperienced observer to mistakenly read the top of the slide for the daily maximum temperature rather than correctly reading the bottom of such slide, a point that El Fadli made in a message to me early on in the investigation”.

With all the pieces of the puzzle now falling into place a vote was taken in January 2012 resulting in a unanimous decision by the WMO committee members to disallow the Azizia record.

As Tom Peterson put it, “The eventual answer seemed so clear and obvious that we evidently must have done a far more in depth investigation than any earlier one.”

Based on that recommendation, Randy and Jose Luis Stella of Argentina, the WMO’s co-Rapporteurs of climate and weather extremes, have rejected the 58ºC temperature extreme measured at El Azizia in 1922. An important aspect of this long investigation was that it just isn’t climatologists and meteorologists changing their minds. It goes beyond that. This investigation demonstrates that, because of continued improvements in meteorology and climatology, researchers can now reanalyze past weather records in much more detail and with greater precision than ever before. The end result is an even better set of data for analysis of important global and regional questions involving climate change. Additionally, it shows the effectiveness of truly global cooperation and analysis. Consequently, the WMO assessment is that the official highest recorded surface temperature of 56.7°C (134°F) was measured on 10 July 1913 at Greenland Ranch (Death Valley) CA USA.