By Chris Cappella, AMS

It began with a whisper. And ended in smothered silence for millions.

Slideshow of blizzard photos.

I’ll never forget seeing tiny snowflakes blowing down Ocean Avenue in our small sea-side suburb of New Haven. In my hometown of West Haven, on the south shore of central Connecticut overlooking Long Island Sound, when snow fell it usually just stuck, firmly. On everything. The relative warm ocean water often changes our winter events to miserably cold rain. It never allows for dry, powdery snow. Or so I thought. Today—February 6, 1978—would be different. Far, far different. Than many of us hearty New Englanders, as we’re known, had ever seen. For that silky soft sinewy snow I was seeing in the infancy of this storm would grow into a furious blizzard and bury the region—a blizzard by which all others there since would be measured.

The tiny flakes blew into snowy tendrils that would side-wind down the road until they escaped the wind. And pile into miniature snowdrifts. A harbinger of things to come, but on a gigantic scale. This was the beginning of the epic Blizzard of ’78 in New England. Over the next 30+ hours, the snow would fall heavier than anything I—and most of us in the Northeast—had ever experienced. Sideways snow. Two to three inches an hour. For hours and hours. Blowing in winds gusting over 50 mph region-wide, and to hurricane force along the coast. 110 mph Scituate, Massachusetts. Snow so deep even as a 12-year-old I would struggle to walk in it. Drifts so large and deep they dwarfed entire houses. You could jump off second-story rooftops into them. And my friends and I did. Off our grammar school roof. Even its 45-foot high gymnasium roof. Weightless, for a second or two. And then: whump! We’d completely disappear in snowdrifts 10-15 feet tall.

Buried barely begins to describe the otherworldly landscape. Nearly all human life in the region would slow down and eventually grind to a halt. Thousands of people stranded on roadways as blinding snow enveloped everything, too quickly to make an escape. Governor Ella T. Grasso ordered all vehicles off the roads. We capitalized on it. Building giant snow forts with tunnels in the mountains of snow piled on sides of our road. Only once, though, did we recklessly dive into our snow tunnels to escape an oncoming snowplow. Luckily for us kids the snowplow only took out the last 3-4 feet of our tunnels, sparing us certain death. By snowplow.

Legendary Boston meteorologist, Harvey Leonard, who was just 29 then, remembers seeing “big potential” for a major snowstorm coming together in the Northeast four days beforehand—a lead-time “close to unheard of” in those days, he told The Boston Globe in a recent article chronicling the blizzard.

“As a person — not only a meteorologist, but somebody who really loves weather and is fascinated by storms, particularly winter storms — it was pretty amazing to see what was unfolding. ‘78 still stands as the most powerful and wide-reaching storm that I’ve ever been involved in forecasting and experiencing.”

The defacto “official” website devoted to the storm—blizzardof78.org—put together by amateur historian Matt Bowling describes how a failed forecast weeks earlier set up a situation in which people headed to work and school that Monday morning, February 6, as if just a routine snowfall was expected.

It is safe to say that by the time February 6th, 1978 came along, New Englanders had been pretty-well trained to not pay much attention to the weathermen. It had been a difficult winter already. On January 21st, as most forecasters predicted only rain, New England had been blanketed by a major league snowstorm that dropped 21 inches of snow in Massachusetts and downed a record number of power lines in Rhode Island. This forerunner to the Blizzard of ’78 had brought so much snow that the roof of the Hartford Civic Center actually collapsed from the weight. When forecasters began predicting another big storm, nobody thought too much of it.

In a series of quotes gathered and posted to the site, WTNH-TV meteorologist and Western Connecticut State University professor Dr. Mel Goldstein continues this theme, describing why there was skepticism about the forecast for the storm:

Back in 1978 we did not have the accuracy of the computer models that we have today. And in 1978 there was a brand new computer model that came out and it was predicting the storm to be pretty much the magnitude it turned out to be. But because the computer model was brand new, people did not have confidence in it. And so there was some question whether or not people wanted to buy into the kind of product that it was delivering. To me it looked very reasonable … and I took my little bag of clothes and I moved into Western Connecticut State College weather lab and I said, ‘I’m going to be here for a few days and there’s no question about that. It’s in the logbook on that day: ‘a granddaddy of a snowstorm is coming our way.’

And in another Boston Globe article, noted weather columnist David Epstein wrote four years earlier about The meteorology behind the blizzard of February 6-7th 1978. In his article he reiterates how so many were caught off guard by the blizzard.

Computer models were still relatively new and a series of busted forecasts left many people skeptical that a big storm was actually coming. On the morning of the 6th, snow was suppose to start prior to the morning commute. However, when folks awoke and saw the snow hadn’t begun many of them decided it was another busted forecast and went to work. These same people would then try to get home that afternoon while the blizzard was fully underway.

A search on YouTube turns up numerous documentaries on the Blizzard of ’78, including “Blizzard of ’78,” below, on Leonard’s station WCVB.

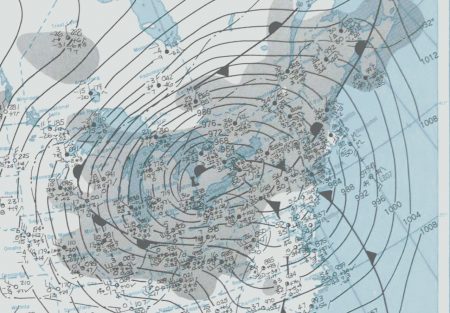

Remarkably, New England’s Blizzard of ’78—with its record snowfall observations in Boston and Providence and its utter destruction along the Massachusetts coast as powerful winds slammed monster waves ashore through four tide cycles—came on the heels of a nearly equally intense blizzard that slammed the Midwest on January 25-27. That Blizzard of ’78 became known as the White Hurricane, with wind gusts of 100 mph and feet of snow shutting down states from Wisconsin to Ohio. It set pressure records (956.0 mb in Mount Clemens, Michigan—third lowest non-tropical atmospheric pressure ever recorded in the Unites States) and remains the worst blizzard on record in Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan.

Its magnitude was summed up in a statement by NWS Detroit meteorologist C. R. Snider on January 30, 1978:

The most extensive and very nearly the most severe blizzard in Michigan history raged January 26, 1978 and into part of Friday January 27. About 20 people died as a direct or indirect result of the storm, most due to heart attacks or traffic accidents. At least one person died of exposure in a stranded automobile. Many were hospitalized for exposure, mostly from homes that lost power and heat. About 100,000 cars were abandoned on Michigan highways, most of them in the southeast part of the state.

Nearly three dozen times as many cars abandoned—and that was in just one Midwestern state.

To some, Blizzard of ’78 conjures up memories of a similar yet completely different storm.

I remember staying up most of the night of January 26, 1978, mesmerized by the explosive deepening of this storm from my weather office at KDAL TV in Duluth, Minnesota. Nothing like the 3 hourly surface analysis had ever emanated from my office Alden Electronics Weather Fax machine. I called up the CBS network and told them to monitor news from their affiliates in the southern and central Great Lakes area. After getting home, I heard outstanding, detailed coverage by staff meteorologists from WJR Detroit, and WWWE Cleveland on my 6 transistor radio (wish I remembered their names!). They were outstanding in clarity, detail, the timing of the sequence of events that would unfold, and in the confident urgency/ you need to know this type of delivery in which they spoke. A remarkable storm, happy to have had a cat bird view of it, and proud of the meteorologists that served their communities.